Table of Contents

Credits

Hosts: Sarah May Johnson, Sara Dong

Guest: Fani Ladomenou

Writing: Justin Penner

Producing/Editing/Cover Art/Infographics: Sara Dong

Our Guests

Guest Consultant

Fani Ladomenou, MD PhD

Fani Ladomenou graduated from the School of Medicine, University of Crete (1998-2004) with distinctions and obtained a Doctoral Degree in Medicine (2011, Paediatrics). She has served as a Fellow in Paediatric Infectious Diseases/Immunology in Academic Hospitals in the UK (London, Great Ormond Street Hospital and Newcastle upon Tyne, Great North Children Hospital) and has also worked as a consultant in Paediatric Immunology & Infectious Diseases at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London, UK.

She has been a clinician in Paediatrics since 2012 and is currently caring for sick children at Venizeleion General Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece, being responsible for the Paediatric Infectious Diseases/Immunology service. She has completed her postgraduate studies in the field of Paediatric Infectious Diseases at the University of Oxford, UK and is actively involved in medical research focusing on Infectious Diseases and Paediatrics and has relevant publications in peer-reviewed international journals. She served as a Young Board Representative for the European Society of Pediatric Infectious Diseases (ESPID) between 2018 and 2021.

Guest Co-Host

Sarah May Johnson BSc (Hons) MBBS MRCPCH DTM&H

Sarah May Johnson is a current paediatric registrar of infectious diseases, immunology, and bone marrow transplant at Great Ormond Hospital. Sarah was awarded her first undergraduate degree from UCL- a First Class Psychology BSc with a First in Statistics in 2006. She completed a year of ass istant psychology training at Great Ormond Street Hospital before starting her graduate entry medical degree at St George’s University of London in 2007. From 2003-2011 Sarah had been working as a mental health nursing assistance in young people units which instigated her interest in adolescent health.

Sarah was awarded a Distinction in Clinical Practice for her MBBS in 2011. She completed her Foundation Training in London in 2013 and progressed straight into paediatric training. She is a London School of Paediatrics trainee and was awarded her MRCPCH in 2015. Sarah has previously volunteered as a paediatrician with NGOs in Nepal, Haiti and in refugee camps in Greece. This volunteer work and her registrar posts at Great Ormond Street Hospital in infectious diseases, immunology and bone marrow transplant sparked her interest in global health and infectious diseases. She went on to be awarded a Diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (DTM&H) at The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) in 2017. More recently she has passed her generic instructor course for APLS and NLS. Sarah was awarded a Wellcome Trust Global Health Research Fellowship in 2019 to explore adolescent TB. In her spare time she loves to bake, knit and sew.

Culture

Sarah shared her recent knitting projects

Fani recommended a book named The Island by Victoria Hislop. It is set on the island of Spinalonga (near Crete), where a young woman learns about the history of a deserted island that was Greece’s former leprosy colony.

Consult Notes

Case Summary

A mother and neonate pair fall acutely ill. 32 yo woman who developed fever and gastrointestinal symptoms. Her baby born at 39+1 weeks who developed fever/sepsis, seizures, hepatic injury, and vesicular rash consistent with neonatal HSV infection.

Key Points

This episode focused on neonatal herpes simplex (HSV) infection. Let’s start with the key resources!

Quick virology review!

- HSV = large enveloped double stranded DNA virus

- Member of Herpesviridae > subfamily Alphaherpesviridae

- HSV-1 and HSV-2 both exist as two distinct types > but both HSV-1 and HSV-2 can cause neonatal HSV disease

- HSV 1 and 2 establish latency after primary infection

Epidemiology/Transmission of neonatal HSV

HSV is transmitted to a neonate via the pathways noted to the right. Click the toggle for more info!

- Most often – during birth through infected maternal genital tract

- Less common – Ascending infection through ruptured or apparently intact amniotic membranes

- Most often – from nongenital infection (eg mouth or hands) from parent, sibling, or other caregiver

- Although this practice is rare, there have been cases reported of neonatal HSV infection after contact between mouth of religious circumciser (“mohel”) to infant penis during ritual Jewish circumcisions that include direct orogenital suction (metzitzah b’peh)

- A review of neonatal HSV-1 and ritual circumcision with oral suction here: Brian F. Leas, Craig A. Umscheid, Neonatal Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Infection and Jewish Ritual Circumcision With Oral Suction: A Systematic Review, Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, Volume 4, Issue 2, June 2015, Pages 126–131, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpids/piu075

- The accompanying response: Berman D, Breuer B, Federgruen A. Response to Recent Review of Literature on Transmission of Neonatal Herpes Through Ritual Circumcision With Oral Suction. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2015;4(3):284-285. doi:10.1093/jpids/piu111

- Rare!

- Causing congenital malformations

Factors that influence the risk of perinatal transmission include:

- Type of maternal HSV infection

- The risk of transmission to a neonate born to a mother who acquires primary genital HSV infection near time of delivery estimated 25-60%

- The risk of transmission to a neonate born to a mother shedding HSV as result of reactivation acquired during first half of pregnancy or earlier is less than 2%

- Maternal HSV antibody status

- Duration of rupture of membranes (higher risk of >=4 hrs)

- Integrity of baby mucocutaneous barriers (such as use of fetal scalp monitors)

- Mode of delivery (vaginal >> cesarean)

*More than 75% of infants who contract HSV infection are born to women with no history of clinical findings suggestive of genital HSV infection during or preceding pregnancy

Lack of history of maternal genital HSV infection does not preclude diagnosis of neonatal HSV disease

Some resources:

- Caviness AC, Demmler GJ, Selwyn BJ. Clinical and laboratory features of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection: a case-control study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(5):425-430. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181646d95

- Corey L, Wald A. Maternal and neonatal herpes simplex virus infections [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2009 Dec 31;361(27):2681]. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1376-1385. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0807633

Clinical manifestations of neonatal HSV disease

In neonates, HSV infection presentations are described as:

- Disseminated disease (~25%)

- Multiple organs involved, such as

- Liver: hepatitis, ascites, direct hyperbilirubinemia >> can progress to liver failure

- Lungs: pneumonia, hemorrhagic pneumonitis

- CNS

- Cardiac: myocarditis and myocardial dysfunction

- Bone marrow: DIC, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia

- AKI

- Necrotizing enterocolitis

- Central nervous system (CNS) is involved in 60-75% of these cases

- ! Consider in neonates with sepsis syndrome with negative culture results, severe liver dysfunction, consumptive coagulopathy, or suspected viral pneumonia (especially hemorrhagic pneumonia)

- Multiple organs involved, such as

- Localized CNS disease (30%) = neonatl HSV meningoencephalitis

- With or without skin, eye, or mouth involvement

- Seizures (focal or generalized), lethargy, irritability, tremors, poor feeding, temperature instability, full fontanel

- CSF: mononuclear cell pleocytosis, normal or low glucose, mildly elevated protein (but can have normal CSF studies early in disease)

- Localized SEM disease (45%)

- Disease localized to skin, eyes, and/or mouth

- >80% of these neonates will have characteristic skin vesicles

- High risk of progression to CNS or disseminated disease if not treated

In the absence of skin lesions, the diagnosis of neonatal HSV infection is challenging and requires a high index of suspicion

- ~2 / 3 of neonates with disseminated or CNS disease will also have skin lesions (but they may not be present at time of onset of symptoms)

- HSV should be considered in neonates with fever (especially in first 3 weeks of life), vesicular rash, or abnormal CSF findings (especially if seizures present or during a time when enteroviruses are not circulating in the community)

- Asymptomatic HSV infection is exceedingly rare in neonates

- Recurrent skin lesions occur in ~50% of survivors, often within 1-2 weeks of completing the initial treatment course of IV acyclovir

Initial signs of HSV can occurs anytime between birth and 6 weeks of age

- Infants with disseminated disease and SEM disease usually have earlier onset (1-2nd weeks of life)

- CNS disease usually presents between 2nd-3rd week of life

Intrauterine or congenital HSV infection is rare, but a few notes:

- Intrauterine infection due to maternal primary infection and viremia

- Associated with placental infarcts, necrotizing calcifying funisitis, plasma cell deciduitis, lymphoplasmacytic villitis, hydrops fetalis, fetal in utero demise

- The characteristic triad in survivors of in utero HSV includes skin vesicles/ulcerations/scarring, eye damage, severe CNS manifestations like microcephaly (but occurs in less than a third of cases)

- Intrauterine infection due to ascending infection usually occurs after prolonged rupture of membranes in moms with active HSV lesions but can occur through intact amniotic membranes

- Often mild clinical presentation but can be variable with disseminated disease as well

- Intrauterine infection due to maternal primary infection and viremia

Some references in addition to key resources at top of Consult Notes:

- Kimberlin DW. Herpes simplex virus infections of the newborn. Semin Perinatol. 2007;31(1):19-25. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2007.01.003

- Marquez L, Levy ML, Munoz FM, Palazzi DL. A report of three cases and review of intrauterine herpes simplex virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(2):153-157. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181f55a5c

So have a high clinical suspicion for neonatal HSV infection in neonates and infants up to 6 weeks of age with:

- Sepsis-like illness (fever or hypothermia, irritability, apnea, respiratory distress, hepatomegaly, ascites, and more)

- Persistent fever and negative bacterial cultures

- Vesicular rash

- CSF pleocytosis

- Seizures, focal neurologic signs, abnormal neuroimaging

- Thrombocytopenia

- Elevated liver transaminases or acute liver failure

- Conjunctivitis with watery discharge or painful eye symptoms

Diagnosis & Evaluation

- What tests can we use for detection of HSV?

- Isolation of HSV in traditional or enhanced viral culture

- Cytopathogenic effects typical of HSV are usually observed 1-3 days after inoculation. Cultures that remain negative by day 5 likely will remain negative

- Detection of viral DNA using PCR assays

- PCR assay usually can detect HSV DNA in CSF from neonates with CNS infection

- Detection of viral antigens using rapid direct immunofluorescence assays (DFA)

- **Serology is generally NOT helpful for diagnosis in neonates

- Isolation of HSV in traditional or enhanced viral culture

- For diagnosis of neonatal HSV infection, all of the following specimens should be obtained

- Surface specimen swabs:

- Swab specimens from the conjunctivae, mouth, nasopharynx, anus

- Can use a separate swab for each site, or single swab starting with conjunctivae

- Send for viral culture and/or PCR

- Specimens of skin vesicles

- Swabs/scrapings/aspirate of vesicle fluid if present

- Send for viral culture and/or PCR. DFA of skin lesion scraping may be used but not as sensitive as PCR and culture

- CSF sample should be obtained in all neonates with suspected HSV

- Send for HSV PCR assay (sn 75-100%, sp 71-100%)

- More sensitive than viral culture

- May be negative early in course of illness

- Blood or high protein in CSF may interfere with some PCR assays and produce false negative results

- Send for HSV PCR assay (sn 75-100%, sp 71-100%)

- Whole blood (or plasma) sample for

- HSV PCR assay

- ALT

- Can send other specimens for viral culture or PCR if available (such as tracheal aspirate or peritoneal fluid)

- Surface specimen swabs:

- Positive cultures from any surface site more than 12-24 hrs after birth indicates viral replication and is suggestive of infant infection (therefore risk of progression to neonatal HSV disease rather than mere contamination after intrapartum exposure)

- Surface cultures are positive in >=90% of cases and provide the greatest diagnostic yield (regardless of disease classification)

- Any of 3 forms of neonatal HSV disease can have associated viremia, so a positive whole blood PCR assay result does not define an infant as having disseminated HSV > and therefore should not be used to determine extent of disease or duration of treatment

- No data exist to support use of serial blood PCR assays to monitor response to therapy

- Other studies to obtain to assess for organ involvement and exclude other diseases:

- CBC/diff, liver function tests, BUN/Cr, UA

- Blood and CSF cultures to evaluate for bacterial sepsis

- Ophthalmologic examination

- EEG if suspected to have CNS disease

- Neuroimaging

- CXR if signs of pulmonary involvement

- Abdominal US in those with hepatitis and/or liver failure

- Some additional references to add to those previously noted:

Management of asymptomatic exposed infants

The optimal management of asymptomatic exposed infants exposed to maternal HSV at delivery has not been evaluated in trials, but there are experts/society guidelines on testing and antiviral therapy.

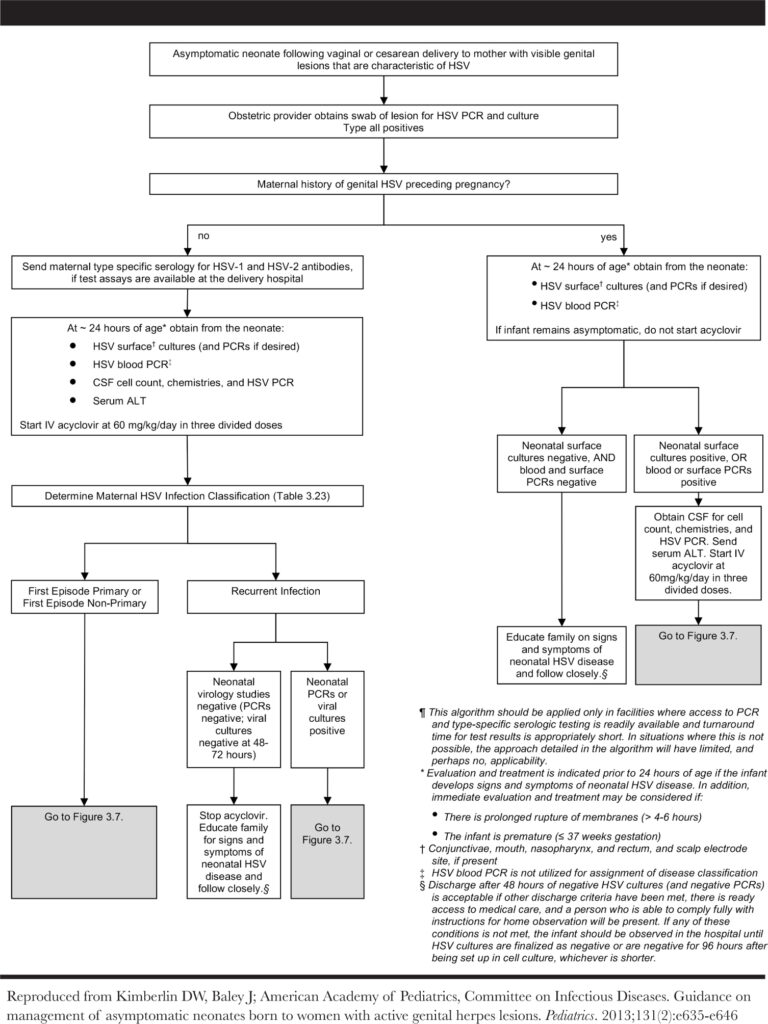

You can find the algorithm below, which can be found as Fig 3.6 in the AAP Red Book HSV Chapter or Fig 2 in the Kimberlin, 2013 paper.

Treatment of neonatal HSV infection

- Treatment of neonatal HSV disease improves survival and outcomes, especially when treated early in course of disease. It shifted one year mortality rates from 85% > 29% in disseminated disease and 50% > 5% in CNS disease.

- Early treatment also prevent progression of SEM disease to CNS or disseminated disease (about half of infants with SEM will progress to CNS or disseminated disease without treatment)

- You can find key trials below. Of note, vidarabine is no longer available in the US and had issues with toxicity

- Kimberlin DW, Lin CY, Jacobs RF, et al. Safety and efficacy of high-dose intravenous acyclovir in the management of neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):230-238. doi:10.1542/peds.108.2.230

- Jones CA, Walker KS, Badawi N. Antiviral agents for treatment of herpes simplex virus infection in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009(3):CD004206. Published 2009 Jul 8. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004206.pub2

- Whitley R, Arvin A, Prober C, et al. A controlled trial comparing vidarabine with acyclovir in neonatal herpes simplex virus infection. Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(7):444-449. doi:10.1056/NEJM199102143240703

- IV acyclovir = treatment of choice for neonatal HSV infections

- Dosage: 60 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses

- Duration:

- SEM disease: 14 days

- CNS or disseminated disease: minimum of 21 days

- All infants with CNS involvement should have repeat LP near end of therapy to document that CSF is negative for HSV DNA on PCR assay

- In event that PCR result remains positive near end of treatment, should extend IV acyclovir for another week >> then repeat CSF assay again

- IV antiviral therapy should not be stopped until CSF PCR result for HSV DNA is negative

- Infants with any classification of neonatal HSV disease should receive oral acyclovir suppression

- Dosage: 300 mg/m2/dose, 3 times daily

- Duration: 6 months after completion of IV therapy for acute disease

- Long-term suppressive therapy up to one year has been used in patients with HSV keratitis because of risk of impaired vision with reactivation

- Monitoring:

- Adjust dose monthly to account for growth

- Absolute neutrophil counts at 2 wks, 4 wks, and then monthly afterwards

- Longer durations or higher doses of antiviral suppression do not further improve neurodevelopmental outcomes

- Valacyclovir has not been studied for longer than 5 days in young infants, so should not be used routinely for suppression in this age group

- Based on this RCT: Kimberlin DW, Whitley RJ, Wan W, et al. Oral acyclovir suppression and neurodevelopment after neonatal herpes. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(14):1284-1292. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003509

- Topical ophthalmic drug (1% trifluridine or 0.15% ganciclovir) along with IV therapy may be indicated in infants with ocular involvement attributable to HSV infection

- Additional references:

Prevention of neonatal infection

- ACOG recommends that women with active recurrent genital herpes be offered suppressive antiviral therapy at or beyond 36 weeks of gestation

- However cases of neonatal HSV disease have occurred among infants born to mothers who received prophylaxis

- Management of Genital Herpes in Pregnancy: ACOG Practice Bulletinacog Practice Bulletin, Number 220. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(5):e193-e202. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003840

- The risk of transmitting HSV to newborn during delivery is influenced by mother’s classification of HSV infection as we noted earlier in the post:

- Women with primary genital HSV infection who are shedding at delivery are 10-30 times more likely to transmit to newborn (compared to women with recurrent genital infection)

- AAP developed algorithms to address evaluation and management of asymptomatic neonates following vaginal or cesarean delivery to women with active genital lesions (figure in evaluation section)

- These outline one approach to management but may not be feasible in locations with limited access to PCR assays or type-specific serologic tests

- A key point to remember: if an infant develops symptoms that could indicate neonatal HSV disease anywhere on the algorithm, they should receive full diagnostic evaluation and initiation of IV acyclovir!!

Early-onset neonatal sepsis

Early onset neonatal sepsis is usually defined as a clinical syndrome that presents within the first 7 days of birth. There is not a clear consensus definition of neonatal sepsis, but this classification/timeframe is generally used. There are some experts that would use 72 hrs of life as most infants with early-onset sepsis will present during their birth hospitalization

- Early onset infection is usually due to vertical transmission by ascending contaminated amniotic fluid or during vaginal delivery due to bacteria in mom’s genital tract.

- Maternal chorioamnionitis is a well recognized risk factor for early onset sepsis

Fani gave a great overview of typical pathogens that might cause early onset neonatal infection

- Group B Streptococcus (GBS) and E.coli are the primary culprits of early (and late!) onset sepsis

- Other less common bacterial pathogens might include:

- Enterobacter

- Enterococcus

- Listeria

- Nontypeable H.influenzae

- Other gram negative bacilli (Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Citrobacter, Pseudomonas)

- Staph aureus

- Viridans strep

- Nonbacterial considerations include:

- HSV!

- Enterovirus

- Parechovirus

- Candida

Fani also spoke about how the guidelines for GBS screening vary amongst countries. You can use the resources below to read a bit more about the available evidence that has led to variation in this practice

- Fani mentioned that in Greece where she practices GBS screening is recommended by national guidelines, but often not performed in practice

- In the UK:

- The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommend against universal GBS screening. They recommend intrapartum bacterial prophylaxis to women with previous baby with early or late onset GBS disease, but they do not recommend antenatal treatment before the onset of labor for positive GBS screen from vaginal or rectal swab (carriage)

- Find the Green-top Guideline from the Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists & Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health here

- The 2021 NICE guideline “Neonatal infection: antibiotics for prevention and treatment” here

- The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommend against universal GBS screening. They recommend intrapartum bacterial prophylaxis to women with previous baby with early or late onset GBS disease, but they do not recommend antenatal treatment before the onset of labor for positive GBS screen from vaginal or rectal swab (carriage)

- In the US:

- In Canada:

- Recommended to offer screening and provide IAP at onset of labor or rupture of membranes

- Find the 2018 reaffirmed Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada (SOGC) Clinical Practice Guidelines here

In the rare event of failure to respond to IV acyclovir…

This case featured a period of dual therapy for persistent viraemia due to lack of response in HSV PCR. This is very rare, but Fani pointed out two possibilities:

- Potential underlying immunodeficiency

- Inborn errors have been associated with susceptibility to HSV, such as severe combined immune deficiency (SCID), GATA2 deficiency, DOCK8 deficiency, IL-12 receptor deficiency, or IFN-gamma receptor deficiency

- Alternatively, could have HSV resistance to acyclovir, but this is quite rare (particularly if mom has primary infection). HSV isolates can be studied for susceptibility in these cases

CCC Series Art & Infographics

Goal

Listeners will be able to approach the diagnosis and management of neonatal HSV infection

Learning Objectives

After listening to this episode, listeners will be able to:

- Define the three major classifications of neonatal HSV disease

- List the recommended diagnostic evaluation for suspected neonatal HSV disease

- Describe the treatment regimen and monitoring recommended for children with neonatal HSV disease

Disclosures

Our guest (Fani Ladomenou) as well as Febrile podcast and hosts report no relevant financial disclosures

Citation

Ladomenou, F., Dong, S. “#41: Curious Congenital Conundrums – A Cold Sore Crisis”. Febrile: A Cultured Podcast. https://player.captivate.fm/episode/b348bcdd-7248-4e04-9681-527b5bf8ec41