Table of Contents

Credits

Hosts: Cesar Berto, Sara Dong

Guest: Shweta Anjan

Writing/Infographics: Cesar Berto, Sara Dong

Producing/Editing/Cover Art: Sara Dong

Our Guests

Guest Consultant

Shweta Anjan, MD

Dr. Shweta Anjan is a transplant infectious disease physician at the Miami Transplant Institute. She is an assistant professor in clinical medicine and associate program director of the transplant infectious disease fellowship program at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. Dr. Anjan went to medical school at Kasturba Medical College Manipal in India. She completed her internal medicine residency from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center; infectious disease and transplant infectious disease fellowships at University of Miami – Jackson Memorial Hospital and has been there since, as faculty. Dr. Anjan is also a public voices fellow with the OpEd Project. She enjoys spending time outdoors with her dog Biscuit and gardening (with gloves!) obviously.

Guest Co-Host

Cesar Berto, MD

Dr. Cesar Berto is a chief resident at Jacobi Medical Center / Albert Einstein College of Medicine and an incoming ID fellow at the Massachusetts General Hospital/Brigham & Women’s Hospital fellowship program.

Culture

Cesar recommended “Come from Away”

Shweta has been enjoying finding new pop music from her Peloton rides

Consult Notes

Consult Q

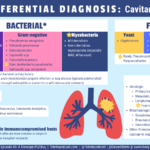

Recommendations for work-up of cavitary lung lesion

Case Summary

60 year old female s/p bilateral lung transplantation who was found to have disseminated Nocardia abscessus infection.

Key Points

Shweta walked through her approach to a solid organ transplant recipient with cavitary lung and skin lesions.

- Have you checked out The Transplantation Society / Transplant ID Clinical Pathological Webinar series before? There was a session on an SOT patient with skin lesions from Oct 2021 available here for members of TTS/TID

Key resource alert!

- The AST ID COP Guidelines are a great tool and were referenced throughout the episode: Restrepo A, Clark NM; Infectious Diseases Community of Practice of the American Society of Transplantation. Nocardia infections in solid organ transplantation: Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Community of Practice of the American Society of Transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2019;33(9):e13509. doi:10.1111/ctr.13509

- A classic: Fishman JA. Infection in solid-organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(25):2601-2614. doi:10.1056/NEJMra064928

A quick review of micro for Nocardia spp

- Ubiquitous gram-positive acid-fast, catalase-positive bacteria

- Grows as filamentous branching rods

- There are >80 Nocardia spp, and there is some variability in identifying which spp cause the most human disease. Ones to probably keep in mind include:

- N.nova

- N.brasiliensis

- N.farcinica

- N.cyriacigeorgica

- N.abscessus

What are the epidemiology/risk factors that we need to consider with Nocardia?

- Nocardia are found worldwide in soil, water (fresh or salt), and decaying vegetation

- Transmission occurs primarily through inhalation from an environmental source

- It has been observed that dry windy climates like in the Southwest US may facilitate aerosolization and dispersal of organisms >> prevalence of infection appears to vary by geography

- Other sources of transmission include:

- Penetrating cutaneous injuries

- Ingestion

- Uncommon but reported previously, there have been clusters of nosocomial infection too

- Majority of Nocardia infections will occur in immunocompromised patients or those with chronic lung disease

- The immune response to Nocardia is primarily T-cell mediated, so immunocompromised hosts at particular risk include: solid organ transplant, hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, persons with HIV and CD4 <100, malignancy, chronic steroid therapy, idiopathic CD4 T-cell lymphopenia, chronic granulomatous disease

- Other medications such as rituximab, alemtuzumab, TNF-alpha blocking therapies are also important to consider as risk factors

- As Shweta mentioned, the incidence of Nocardia in solid organ transplant recipients is estimated to be about 1-3%, depending on the series

- It appears that there are greater rates of nocardial infection in lung transplant recipients

- Nocardial infection in transplant recipients typically occurs in first 1-2 years post-transplant (although rare to occur within the first month)

- Time to infection may vary by organ

- Remember that augmented immunosuppression for rejection may also be a risk factor

- A few other noted risk factors have included:

- CMV disease in the last 6 months

- Age and length of ICU stay after transplant

Some references:

- AST ID COP Guidelines

- Coussement J, Lebeaux D, van Delden C, et al. Nocardia Infection in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: A Multicenter European Case-control Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(3):338-345. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw241

- Lebeaux D, Morelon E, Suarez F, et al. Nocardiosis in transplant recipients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33(5):689-702. doi:10.1007/s10096-013-2015-5

- Majeed A, Beatty N, Iftikhar A, et al. A 20-year experience with nocardiosis in solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients in the Southwestern United States: A single-center study. Transpl Infect Dis. 2018;20(4):e12904. doi:10.1111/tid.12904

- Peleg AY, Husain S, Qureshi ZA, et al. Risk factors, clinical characteristics, and outcome of Nocardia infection in organ transplant recipients: a matched case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(10):1307-1314. doi:10.1086/514340

What is the typical clinical presentation of Nocardia infection in solid organ transplant recipients?

- As mentioned in the previous section, infection in transplant recipients typically occurs in the first 1-2 years post-transplant (although this can vary). Course is generally subacute/indolent

- Lungs are the primary site of infection: shortness of breath, dry or productive cough, hemoptysis, fever, weight loss, asthenia

- Constitutional symptoms without respiratory symptoms may occur

- Nocardia has a special tropism for neural tissue >> CNS infection usually leads to single or multiple parenchymal brain abscesses

- May present as headache, seizure, meningitis, focal neurologic deficit, generalized nonspecific complaints

- Always consider brain involvement in immunocompromised hosts with pulmonary nocardiosis!!

- Nocardial meningitis is less frequent than brain abscess but may occur

- Cutaneous disease can present in a variety of patterns:

- Primary cutaneous disease

- Most common skin lesions: ulcers, cellulitis, subcutaneous nodules, abscess

- This can be due to traumatic inoculation such as penetrating injury during gardening, farming, or trauma

- Likely will appear just like what you’d expect from pyogenic bacteria like Staph aureus or Grp A Strep

- Lymphocutaneous disease can occur leading to nodular lymphangitis (similar to Sporothrix schenckii pattern, also called “sporotrichoid nocardiosis”)

- Disseminated disease can lead to cutaneous manifestations through hematogenous spread

- Lastly, Nocardia can cause mycetoma (chronic infection similar to eumycetoma seen with fungal infection). N.brasiliensis is usually the culprit organism in these cases

- Primary cutaneous disease

- Disseminated infection (at least two noncontiguous organs involved) may occur in transplant recipients

- Bloodstream and CNS are most often involved

- Other possible sites for dissemination that occur include: skin, eyes, adrenal gland, kidneys, bone/joint

- Less common sites: epididymo-orchitis, pericarditis, liver abscess

- Although it has propensity to disseminate hematogenously, the organism is not usually found in blood cultures. When it is found to cause bacteremia, it is often associated with central venous catheters

Diagnosis of Nocardial infections

Imaging is often the piece of data that you get back first after the history. CXR or CT in setting of pulmonary disease usually demonstrates: irregular nodular lesions +/- cavitation

- Sometimes a “halo sign” may be evident

- Other appearances may occur though: diffuse consolidative or interstitial infiltrates, pleural effusion

Extrapulmonary disease complicates up to 50% of cases of pulmonary nocardiosis >> so a diagnosis of Nocardia pulmonary infection should prompt evaluation for disseminated disease!

- Local spread to contiguous structures including the chest wall from pulmonary infection has been observed. It does not obey tissue planes as Shweta discussed, prompting our episode title!

- Hematogenous dissemination is not uncommon

- Further investigation typically includes MRI brain to exclude cerebral abscess (up to ⅓ of cases have CNS involvement)

Nocardia should always be considered on your differential for a patient with nodular lesions of the lung and brain! Early recognition is critical to achieve good outcomes

Definitive diagnosis relies on isolation of organism on culture from a suspected site of infection

- As emphasized in the episode, it is important to obtain lung or skin biopsies to confirm the diagnosis

- Biopsy of brain abscesses while preferred may not be feasible

Although Nocardia can colonize the respiratory tract and contaminate clinical specimens in certain patients (usually those with underlying lung disease and no immunosuppression), isolation of Nocardia from a transplant or immunocompromised patient should always be investigated!

Organisms appear in tissue as gram positive branching and beaded rods surrounded by pyogenic inflammatory reaction

Grows in nonselective media, but you should inform your lab of the possibility as they can try additional techniques

- Growth might be obscured in mixed specimens like sputum

- Cultures should be incubated for longer time period and yield of culture for Nocardia can be increased by use of selective media (e.g. Thayer Martin agar with antibiotics)

- Nocardia may take 2 days to several weeks to grow in culture

- Colonies appear chalky white if producing aerial hyphae

Determining the species and susceptibility pattern of Nocardia is important for management! The AST ID COP guidelines recommend obtaining speciation of clinical isolates to guide antimicrobial therapy.

- Traditional phenotypic methods for identifying spp are inadequate, and isolates should be speciated at qualified labs by molecular methods

Treatment & Management of Nocardia infection

- Surgical debridement may be required in some cases

- Initial selection of antibiotics should consider:

- Site and severity of disease

- Potential for drug interactions

- Adverse effects

- Species of Nocardia

- Antimicrobial susceptibility testing is strongly recommended, especially in the setting of disseminated infection, treatment failure or relapse, when non-sulfonamide-based therapy is planned, or when newly identified species are isolated. You can view Table 1 in the AST ID COP guidelines for an overview of various species susceptibility patterns.

- Want to know which antibiotics to test against – check out CLSI reference for Nocardia spp susceptibility testing in M24: https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m24/

- Check out Table 2 from the AST ID COP guidelines for suggested empiric therapy for Nocardia infections in transplant patients

Disease | Empiric therapy | Alternative | Duration of therapy |

Pulmonary – stable | TMP-SMX | Imipenem + amikacin or ceftriaxone or minocycline or linezolid | 6-12 mo |

Pulmonary – critical | Imipenem + amikacin or TMP-SMX | Linezolid | 6-12 mo |

Cerebral | Imipenem + amikacin or TMP-SMX | Linezolid or ceftriaxone or cefotaxime or minocycline | Parenteral therapy 3-6 wk then change to oral therapy for at least 12 mo of treatment |

Dissemianted (>1 organ +/- cerebral disease) | Imipenem + amikacin or TMP-SMX | Ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, linezolid, or minocycline after initial therapy | 9-12 mo |

- There are no controlled trials comparing treatment regimens for nocardiosis. Evidence for the treatment recommendations are based on animal studies, case series, and case reports

- So the table is just a guide. Treatment ultimately depends on antimicrobial susceptibility, severity of illness, immunosuppression, and allergy history!

- TMP-SMX is generally the preferred agent in treating most nocardial infections

- Monotherapy may be adequate for localized skin infection or stable patients with pneumonia

- Duration of TMP-SMX use has been associated with lower risk of relapse or death (see Tashiro reference below)

- Some species such as N.farcinica and N.pseudobrasiliensis have high grade resistance to sulfonamides

- There is likely a range of effective doses, but recommended treatment dosing is 15 mg/kg/d orally or IV in 2-4 divided doses

- Imipenem, ceftriaxone, or linezolid are options for first-line treatment of Nocardia infection in those with sulfa allergy

- Combination therapy is used for those that are critically ill, have severe pulmonary infection, have disseminated or CNS disease, and those who are immunocompromised >> at least 2 agents (imipenem + amikacin or TMP-SMX) for initial therapy

- This is based mostly on synergy data in animal models and the high mortality

- Three-drug therapy has been used for life-threatening disease (TMP-SMX + imipenem + amikacin, linezolid, or ceftriaxone)

- There isn’t really any data on this combination improving outcomes so far

- Duration of therapy will be prolonged and depends on the site and extent of infection

- Duration should be extended if there is augmentation of immunosuppression

- Monitoring should continue for up to 1 year after discontinuation of therapy

References:

- Tashiro H, Takahashi K, Kusaba K, et al. Relationship between the duration of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole treatment and the clinical outcome of pulmonary nocardiosis. Respir Investig. 2018;56(2):166-172. doi:10.1016/j.resinv.2017.11.008

- Uhde KB, Pathak S, McCullum I Jr, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant nocardia isolates, United States, 1995-2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(12):1445-1448. doi:10.1086/657399

How does the use of Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia prophylaxis with TMP-SMX impact nocardial infection?

- TMP-SMX prophylaxis provides additional benefits beyond PJP for prevention of Toxoplasma, Listeria, and other pathogens

- Primary prophylaxis:

- TMP-SMX also appears to reduce the rate of nocardial infection in SOT recipients when used for PJP prophylaxis in the first 6 months post-transplant >> but there have been reports of breakthrough nocardial infections

- There has been breakthrough with TMP-SMX susceptible Nocardia isolates despite TMP-SMX (in Minero, et al & Coussement, et al: ~20% of patients with nocardiosis were on TMP-SMX for PJP prophylaxis and 62-78% of isolates were susceptible to the drug)

- Another consideration would be whether intermittent dosing of TMP-SMX for prophylaxis (2-3x/wk rather than daily) might lead to insufficient levels of drug and breakthrough infections, but breakthrough has occurred despite daily prophylaxis

- Ultimately, the efficacy of prophylaxis likely also depends on antimicrobial resistance, post-transplant immunosuppression, and other comorbidities. While prophylaxis might not prevent all cases of Nocardia infection, it could potentially reduce the severity of infection

- Substituting atovaquone for PJP prophylaxis has been associated with increased incidence of Nocardia in allogeneic HSCT recipients (Molina, et al)

- Secondary prophylaxis:

- Similar to primary ppx, it is also difficult to determine the benefit along with best dose and duration for secondary prophylaxis

- Relapse after initial nocardia infection has been reported, often if therapy was shortened <6 months

- Some centers may choose to continue TMP-SMX for long term prophylaxis to prevent relapse, and the AST ID COP guidelines recommend consideration of 1 DS tablet daily

- An alternative that has been used as well is azithromycin

References

- Coussement J, Lebeaux D, van Delden C, et al. Nocardia Infection in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: A Multicenter European Case-control Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(3):338-345. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw241

- Harris DM, Dumitrascu AG, Chirila RM, et al. Invasive Nocardiosis in Transplant and Nontransplant Patients: 20-Year Experience in a Tertiary Care Center. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(2):298-307. Published 2021 Jan 19. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2020.10.009

- Hemmersbach-Miller M, Stout JE, Woodworth MH, Cox GM, Saullo JL. Nocardia infections in the transplanted host. Transpl Infect Dis. 2018;20(4):e12902. doi:10.1111/tid.12902

- Lebeaux D, Freund R, van Delden C, et al. Outcome and Treatment of Nocardiosis After Solid Organ Transplantation: New Insights From a European Study [published correction appears in Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Oct 15;65(8):1431-1433]. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(10):1396-1405. doi:10.1093/cid/cix124

- Majeed A, Beatty N, Iftikhar A, et al. A 20-year experience with nocardiosis in solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients in the Southwestern United States: A single-center study. Transpl Infect Dis. 2018;20(4):e12904. doi:10.1111/tid.12904

- Minero MV, Marín M, Cercenado E, Rabadán PM, Bouza E, Muñoz P. Nocardiosis at the turn of the century. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009;88(4):250-261. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e3181afa1c8

- Molina A, Winston DJ, Pan D, Schiller GJ. Increased Incidence of Nocardial Infections in an Era of Atovaquone Prophylaxis in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(8):1715-1720. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.03.010

- Peleg AY, Husain S, Qureshi ZA, et al. Risk factors, clinical characteristics, and outcome of Nocardia infection in organ transplant recipients: a matched case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(10):1307-1314. doi:10.1086/514340

- Poonyagariyagorn HK, Gershman A, Avery R, et al. Challenges in the diagnosis and management of Nocardia infections in lung transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10(6):403-408. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3062.2008.00338.x

- Santos M, Gil-Brusola A, Morales P. Infection by Nocardia in solid organ transplantation: thirty years of experience. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(6):2141-2144. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.06.065

- Steinbrink J, Leavens J, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Manifestations and outcomes of nocardia infections: Comparison of immunocompromised and nonimmunocompromised adult patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(40):e12436. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000012436

- Yetmar ZA, Wilson JW, Beam E. Recurrent nocardiosis in solid organ transplant recipients: An evaluation of secondary prophylaxis. Transpl Infect Dis. 2021;23(6):e13753. doi:10.1111/tid.13753

Episode Art & Infographics

Goal

Listeners will be able to diagnose and treat Nocardial infection in a solid organ transplant recipient

Learning Objectives

After listening to this episode, listeners will be able to:

- Describe the epidemiology and risk factors for nocardial infection

- Describe typical clinical manifestations of Nocardia

- Discuss antimicrobial treatment for pulmonary, CNS, or disseminated Nocardia infections

Disclosures

Our guest (Shweta Anjan) as well as Febrile podcast and hosts report no relevant financial disclosures

Citation

Anjan, S., Berto, C., Dong, S. “#45: A Disrespectful Bug”. Febrile: A Cultured Podcast. https://player.captivate.fm/episode/6d6af30b-6815-4dfc-8129-c851db2e214d