Table of Contents

Credits

Hosts: Shilpa Vasishta, Sara Dong

Guest: Christina Coyle

Writing: Shilpa Vasishta, Christina Coyle, Sara Dong

Producing/Editing/Cover Art/Infographics: Sara Dong

Our Guests

Guest Consultant

Christina Coyle, M.D., M.S.

Christina Coyle, M.D., M.S. is a board-certified physician in Infectious Disease and has practiced Tropical Medicine for over twenty-five years in New York City (NYC). She is a Full Professor in the Department of Medicine and Pathology at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and is recognized as an expert in Tropical Medicine. She serves as the Director of the Clinical Infectious Disease Service at Jacobi Medical Center, and oversees the largest Tropical Medicine Clinic in the Bronx, NYC. Since 2007, she has been a site director for GeoSentinel, the global surveillance network of the International Society of Travel Medicine (ISTM) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Dr. Coyle is currently serving as an associate editor for Open Forum in Infectious Diseases (OFID). From 2016 to 2021, she served as a Member of the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Infectious Disease Exam Committee. Dr. Coyle is widely recognized as an expert on larval tapeworms, neurocysticercosis, and echinococcus, serving on both national and international committees for this disease. Since 2017, she has served on the Echinococcal WHO working group. Dr. Coyle is also a content expert for the Center for Disease and Prevention Control (CDC) for all complicated cases of echinococcus. She is a co-author on “Diagnosis and Treatment of Neurocysticercosis: 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH).” She is the principal investigator for a CDC cooperative grant, “Reducing the burden of neglected parasitic infections (NPIs) in the United States through evidence-based prevention and control activities”.

Guest Co-Host

Shilpa Vasishta, MD

Shilpa is a first-year ID fellow at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York with an interest in medical education

Culture

Christina brought her love of ballet and dancing. Shilpa shared a similar item by mentioning tap dancing, her son’s love of the movie Happy Feet, and Savion Glover (an American tap dancer)

Consult Notes

Consult Q

Assistance with evaluation of worsening fevers in a returning traveler

Case Summary

38 year old female who presented with fevers, headache, and nausea who was ultimately diagnosed with severe P.falciparum malaria.

Key Notes

You are called as the fellow for a patient with fever and recent travel! The next few episodes will focus on this scenario. What are the key historical points you want to learn for fever in a returning traveler?

- Geography & Itinerary

- Where did they travel? The geographic area details are critical! Countries visited or passed through (you can still acquire infection in layovers or brief stops!)

- Rural or urban settings? Where were their accommodations (Hotel? Local household? Tent? And so on)

- How long were they there? How long have they been back from the region? You want to get a sense of their itinerary and the time course of symptoms (dates of travel and duration of stay at ALL locations) – so that you can assess if incubation periods and symptoms align when you are considering the case

- Transportation modes

- Where was patient born? Previous travel? You want to think about likelihood that patient has been exposed to certain diseases in the past as well

- What type of traveler are they?

- Did they have any pre-travel evaluations or vaccinations?

- Why did they go? For fun? Business? Visiting friends and family?

- Christina emphasized a few points about VFR (those Visiting Friends and Relatives), which are individuals traveling (such as returning home to own country or spouse/parents country) to visit friends and family in higher infectious risk country than the one they are currently residing in

- These patients are less likely to have pre-travel assessment and more likely to come home with vaccine preventable illnesses

- Leder K, Tong S, Weld L, et al. Illness in travelers visiting friends and relatives: a review of the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(9):1185-1193. doi:10.1086/507893

- Matteelli A, Carvalho AC, Bigoni S. Visiting relatives and friends (VFR), pregnant, and other vulnerable travelers. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2012;26(3):625-635. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2012.07.003

- Bacaner N, Stauffer B, Boulware DR, Walker PF, Keystone JS. Travel medicine considerations for North American immigrants visiting friends and relatives. JAMA. 2004;291(23):2856-2864. doi:10.1001/jama.291.23.2856

- Heywood AE, Zwar N. Improving access and provision of pre-travel healthcare for travellers visiting friends and relatives: a review of the evidence. J Travel Med. 2018;25(1):10.1093/jtm/tay010. doi:10.1093/jtm/tay010

- Exposures during travel?

- Sex and intimate contact (Partners? Use of barrier protection?)

- Arthropod exposure (mosquitos, flies, ticks, fleas, other)

- Seeing or receiving bites?

- Use of insect repellant? How well/often they used? It doesn’t rule out insect bites or diseases like malaria, but can give you a sense of what type of traveler they were

- Use of malaria prophylaxis? Which agent, level of adherence?

- Bed nets or screen?

- Animals or animal products? Animal exposures in living quarters or close proximity? Rodents? Animal bites? Any hunting/skinning?

- Food and water consumption habits, handling/preparation: raw/undercooked/unpasteurized food?

- Water exposures? Fresh water? Swimming? Boating?

- Recreational activities (such as hiking, cave spelunking, archaelogical digs, etc)

- Needle or blood exposure (shared needles, injections, acupuncture, tattoos, body piercing, dental work, transfusions, stitches or surgery)

- Clinical signs and symptoms

- And the usual stuff! Past medical history. Past infections and vaccinations. Medications. Pregnancy

Some key fever in a returning traveler resources mentioned on the show (plus a few others!)

- CDC Travelers’ Health Page and specific Destination pages

- CDC Yellow Book for health information for international travel

- Global TravEpiNet (GTEN) is a network of travel clinics across the US aimed at improving the health of those traveling internationally. They are supported by CDC

- Christina specifically mentioned Heading Home Healthy, which is a program supported by TravEpiNet, Mass General Hospital, and the CDC. Check out the interactive tool to guide travel counseling here!

- GeoSentinel is a worldwide communication and data collection network for surveillance of travel related morbidity (CDC supports; initiated by International Society of Travel Medicine)

- Travax provides info for travel health, but requires a subscription (your local travel clinic team might have access to this though)

- WHO International Travel and Health resources. Both the CDC and WHO websites are places to look for possible information on outbreaks as well

- Review articles:

- Thwaites GE, Day NP. Approach to Fever in the Returning Traveler. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(6):548-560. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1508435

- Ryan ET, Wilson ME, Kain KC. Illness after international travel. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(7):505-516. doi:10.1056/NEJMra020118

- Gautret P, Parola P, Wilson ME. Fever in Returned Travelers. Travel Medicine. 2019;495-504. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-54696-6.00056-2

- Fink D, Wani RS, Johnston V. Fever in the returning traveller. BMJ. 2018;360:j5773. Published 2018 Jan 25. doi:10.1136/bmj.j5773

- There are also comprehensive pages through UpToDate that you can reference as well that breaks down clinical approach by the syndrome, incubation period, exposure history and so on

Christina pointed out a few concepts or frameworks when she encounters this type of case. Here’s a quick summary of some of those:

- She asks herself: (1) what is life threatening? (2) what is treatable? (3) what is transmissible? (do I need to isolate this person)

- The approach to the febrile traveler can be overwhelming, but consider these various schemas when building your differential diagnosis:

- Geographic region(s) of exposure

- Exposure-based

- Syndrome/symptoms-based

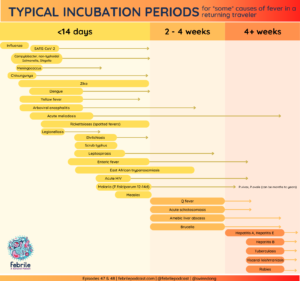

- Fevers related to tropical exposures usually begin during travel or shortly after returning, but they can also be delayed. Defining the illnesses and relevant incubation periods will help you construct the appropriate differential diagnosis

- Risks for infections will vary by geography and season

The epidemiology of fever among travelers

- As Christina mentioned on the show, the most common specific diagnoses in fever in a returning traveler and migrants include malaria and dengue! Others also include mononucleosis, rickettsial infection, and enteric fever (typhoid or paratyphoid fever)

- You can read more in some of these resources, which note information largely from the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network

- Freedman DO, Weld LH, Kozarsky PE, et al. Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill returned travelers [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2006 Aug 31;355(9):967]. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(2):119-130. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051331

- Wilson ME, Weld LH, Boggild A, et al. Fever in returned travelers: results from the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(12):1560-1568. doi:10.1086/518173

- Harvey K, Esposito DH, Han P, et al. Surveillance for travel-related disease–GeoSentinel Surveillance System, United States, 1997-2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62:1-23.

- Leder K, Torresi J, Libman MD, et al. GeoSentinel surveillance of illness in returned travelers, 2007-2011. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(6):456-468. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-6-201303190-00005

- Buss I, Genton B, D’Acremont V. Aetiology of fever in returning travellers and migrants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Travel Med. 2020;27(8):taaa207. doi:10.1093/jtm/taaa207

The rest of these Consult Notes will focus on malaria. Let’s start with a quick overview

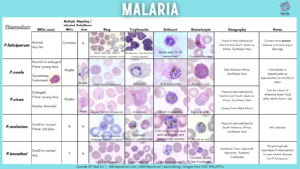

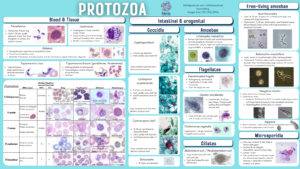

- Caused by 5 species of the genus Plasmodium: falciparum, malariae, vivax, ovale, and knowlesi

- A major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide

- Originally thought to be transmitted by bad air “mala aria” (hence the name of the episode!) >> it was not until late 1800s that physicians identified parasite and demonstrated life cycle

- Disease burden and species prevalence varies by geography and seasonality, and malaria exists year-round in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide

- 90% of disease and death occur in Africa

- Other areas of high incidence include Central America, South America, Southeast Asia, Indian subcontinent, Middle East

- Risk factors for acquisition include environments conducive to the Anopheles mosquitos, such as warm and rainy seasons, shallow collections of water, lack of mosquito netting or other protective measures at home

The malaria life cycle

Vector: female Anopheles mosquitoes, which prefer night-time or pre-dawn biting and transmission

Human infection begins when a malaria-infected female mosquito inoculates sporozoites into human host

- Sporozoites infect hepatocytes, where they mature into schizonts

- [P.vivax and P.ovale have a dormant stage (hypnozoites) which can persist in the liver and cause relapses into the bloodstream]

Schizonts rupture and release merozoites >> which next infect red blood cells (initially visible as ring or trophozoite stage) >> this human “blood stage” is where symptoms occur

- These trophozoites will mature into schizonts, which again rupture and release more merozoites

A portion of merozoites will undergo sexual differentiation into gametocytes (rather than form schizonts) > these gametocytes are ingested by next Anopheles mosquito

- Inside mosquito gut, sporogonic cycle takes place where gametocytes mature and begin cycle of growth and multiplication

Clinical presentation of malaria

The clinical manifestations will vary by species, epidemiology, immunity and age!

- In endemic areas, the groups at highest risk include young children under 6 and pregnant women. In areas where malaria is transmitted throughout the year, older children and adults have some partial immunity and are at relatively low risk for severe disease

- Travelers to malarious areas who have no previous exposure or who have lost their immunity are at very high risk for severe disease if infected with P.falciparum

- Typical incubation periods:

- P.falciparum: 12-14 days (range 7-30 days)

- P.vivax and P.ovale: usually about two weeks, but illness can occur months after initial infection due to residual hepatic hypnozoites. Relapses usually occur within 2-3 years of infection

- P.malariae: 18 days (range 15-35), can occasionally be months to years with low grade asymptomatic infection

- P.knowlesi: 12 days (9-12d)

- Clinical presentation of uncomplicated malaria

- Cardinal symptom = fever (caused by rupture of mature schizonts)

- May follow typical fever cycles known as paroxysms, which are dependant on antibody release as erythrocytes rupture and release merozoites – but fever patterns are not reliable in early infection

- Fever paroxysm patterns are usually described as:

- Every other day or 48 hrs (tertian fever): P.vivax, P.ovale, P.falciparum

- Every third day or 72 hrs (quartan fever): P.malariae

- Every 24 hrs (quotidian fever): P.knowlesi

- Other initial symptoms are often nonspecific: tachycardia, fatigue, headache, myalgias/arthralgias, abdominal pain, cough

- Physical exam may be normal, but might find pallor, splenomegaly, or jaundice

- Labs: parasitemia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated AST/ALT, mild coagulopathy, elevated BUN/Cr

- Cardinal symptom = fever (caused by rupture of mature schizonts)

- *Patients with acute falciparum malaria may have normal physical exam and no fever when first seen*

- What about severe malaria? See the next section!

Severe malaria

- In clinical practice, differentiation between uncomplicated or severe malaria is of utmost importance

- Complicated or severe malaria will have the same symptoms described in uncomplicated malaria, but patients will have evidence of end-organ damage.

- Severe malaria features include:

- Cerebral malaria: encephalopathy/coma, convulsions

- Renal failure / acute tubular necrosis

- Hypoglycemia

- Hemorrhage/hemoglobinuria

- Severe anemia (<=5 g/dL in children <12 yo; <7 g/dL in older children and adults)

- Metabolic acidosis (might see rapid deep breathing on exam clinically)

- Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema

- Shock

- Hyperparasitemia: >=5 % in non-immune travelers; >10% in all patients

- Severity is often correlates with parasitemia although this is not absolute

- P.falciparum can cause severe malaria, while the other species of malaria are much less likely to have complicated disease. There are increasing reports of severe malaria with P.knowlesi though

Malaria Diagnostics

- Microscopy is the standard tool for diagnosis of malaria (visualizing parasites in blood smears). Giemsa-stained thick and thin smears are used to diagnose malaria as well as determine the species and degree of parasitemia

- Certain features on microscopy will help identify the species, but some features might overlap. For example, early P.knowlesi infections can look just like P.falciparum, but as infection progresses, morphology changes to resemble P.malariae.

- You can find more on the key features in the accompanying infographics on malaria

- One other advantage of microscopy is that it also enables diagnosis of hematologic abnormalities and other infections such as filariasis, trypanosomiasis, babesiosis, and others

- The main drawback or limitation is lab training and expertise

- Microscopy cannot reliably detect very low parasitemia or cases when parasite biomass is largely sequestered, as Christina mentioned on the episode. If malaria is suspected and initial smear is negative, additional smears should be examined over the subsequent 2-3 days

- Certain features on microscopy will help identify the species, but some features might overlap. For example, early P.knowlesi infections can look just like P.falciparum, but as infection progresses, morphology changes to resemble P.malariae.

- Rapid diagnostic tests are available that can be run directly on blood samples

- Rapid antigen detection tests usually have a panmalaria target as well as specific P.falciparum target (histidine-rich protein 2; HRP-2)

- Can give a prompt diagnosis, but:

- Provides a qualitative result >> Cannot confirm or quantify degree of parasitemia

- Low sensitivity for non-falciparum malaria and low parasite burden disease

- Moody A. Rapid diagnostic tests for malaria parasites. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15(1):66-78. doi:10.1128/CMR.15.1.66-78.2002

Malaria treatment

The first item is to determine severity of illness. Severe malaria can lead to death within hours, so initiation of antimalarial therapy is critical and an ID emergency

- Treatment of severe/complicated malaria = IV artesunate

- IV therapy recommended for a minimum of 24 hrs and should continue until parasitemia is <1% and patient is able to tolerate oral medication. The median parasite clearance time is <72 hrs but prolonged parasite clearance times have been observed

- Artemisinin medications clear parasitemia faster than quinine and are associated with lower mortality rates

- Adverse effects may include GI symptoms and dizziness (although can be hard to tell how much is their malaria vs drug toxicity). You can read more about delayed onset anemia below as well

- Artesunate is FDA approved in the US and many hospital pharmacies will have a few doses on hand. You can also call the CDC for assistance

- If artesunate is not immediately available, can provide oral antimalarial such as artemether/lumefantrine, atovaquone/proguanil

- Once the IV artesunate arrives, stop the oral medication and administer IV instead

- The other major class of drug for parenteral treatment includes cinchona alkaloids like quinine and quinidine, but IV quinine/quinidine is no longer available in USA

- References about artesunate IV:

- Twomey PS, Smith BL, McDermott C, et al. Intravenous Artesunate for the Treatment of Severe and Complicated Malaria in the United States: Clinical Use Under an Investigational New Drug Protocol. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(7):498-506. doi:10.7326/M15-0910

- Sinclair D, Donegan S, Isba R, Lalloo DG. Artesunate versus quinine for treating severe malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(6):CD005967. Published 2012 Jun 13. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005967.pub4

- Dondorp AM, Fanello CI, Hendriksen IC, et al. Artesunate versus quinine in the treatment of severe falciparum malaria in African children (AQUAMAT): an open-label, randomised trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2011 Jan 8;377(9760):126]. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1647-1657. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61924-1

- Kurth F, Develoux M, Mechain M, et al. Intravenous Artesunate Reduces Parasite Clearance Time, Duration of Intensive Care, and Hospital Treatment in Patients With Severe Malaria in Europe: The TropNet Severe Malaria Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(9):1441-1444. doi:10.1093/cid/civ575

- Dondorp A, Nosten F, Stepniewska K, Day N, White N; South East Asian Quinine Artesunate Malaria Trial (SEAQUAMAT) group. Artesunate versus quinine for treatment of severe falciparum malaria: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9487):717-725. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67176-0

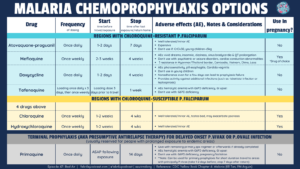

- Treatment of uncomplicated malaria depends on the spp and drug resistance trends

- If chloroquine resistant P.falciparum, you really have 3 main choices:

- Preferred >> Artemether-lumefantin x 3d

- Atovaquone-proguanil x 3d

- Quinine + doxycycline (or clindamycin for pregnancy) x 7d

- (Mefloquine based regimens should only be used if above regimens are not available due to neuropsychiatric effects and resistance in some areas)

- Chloroquine susceptible Plasmodium is only present in a handful of places

- If chloroquine resistant P.falciparum, you really have 3 main choices:

- Other management considerations:

- Dehydration is common! If overhydrate too quickly, patients can be more likely to get noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. Christina recommends hydrating to euvolemia and then matching ins-and-outs

- Don’t forget about treatment of hypoglycemia, especially with new changes in mental status!

- Rule out bacterial co-infection as necessary!

- Repeat clinical assessments ever few hours to monitor for complications

- There is no role for exchange transfusion

- Watch for post-artesunate delayed onset hemolysis

- The mechanism is not completely understood, but artesunate may rapidly kill young ring stages and create pyknotic RBCs that survive briefly >> but then are taken out of circulation leading to delayed onset anemia following treatment anywhere 1-4 weeks afterwards

- Can almost assume that patients with high parasitemia are going to get it

- Monitor repeat Hgb testing at days 7, 14, 30. Anemia will usually improve within 4-8 wks after completion of therapy

- Jauréguiberry S, Ndour PA, Roussel C, et al. Postartesunate delayed hemolysis is a predictable event related to the lifesaving effect of artemisinins. Blood. 2014;124(2):167-175. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-02-555953

- Paczkowski MM, Landman KL, Arguin PM; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update on cases of delayed hemolysis after parenteral artesunate therapy for malaria – United States, 2008 and 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(34):753-755.

- Rolling T, Schmiedel S, Wichmann D, Wittkopf D, Burchard GD, Cramer JP. Post-treatment haemolysis in severe imported malaria after intravenous artesunate: case report of three patients with hyperparasitaemia. Malar J. 2012;11:169. Published 2012 May 17. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-11-169

- Rolling T, Agbenyega T, Issifou S, et al. Delayed hemolysis after treatment with parenteral artesunate in African children with severe malaria–a double-center prospective study. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(12):1921-1928. doi:10.1093/infdis/jit841

- Call the CDC malaria hotline for assistance and questions!

- The CDC Malaria Hotline (770-488-7788) is available Monday through Friday, 9 am to 5 pm EST. Outside these hours, providers should call 770-488-7100 and ask to speak with a CDC Malaria Branch clinician.

Prevention of Malaria

- Below we’ll address some important components of malaria prevention measures

- Travelers to malarious areas need to understand when they are at risk for malaria and that this can be life-threatening

- Although we can provide counseling, travelers should understand that no chemoprophylaxis provides complete protection and that fever during or after travel is a medical emergency

- Counseling for mosquito bite prevention:

- Avoid outdoor exposure during the Anopheles mosquito feeding time between dusk and dawn

- Wear clothing that reduces the amount of exposed skin. Clothing fabric can be treated with permethrin or other residual insecticides

- Wear insect repellent

- Recommended repellants include DEET (30-50%), picaridin, IR3535, oil of lemon eucalyptus

- Sleep in bed nets treated with insecticide

- Stay in well screened or air conditioned rooms

- Chemoprophylaxis (*Must be tailored to travel itineraries and patient circumstances)

- You can check out the chemoprophylaxis table for more info about available drugs

- No chemoprophylaxis guarantees complete protection!

- Reminder of options available to pregnant patients: mefloquine, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine

- Will note that we have focused on travelers, but other keys in endemic areas include eliminating standing water, avoiding being outside during peak hours, etc.

- A few references:

- Lupi E, Hatz C, Schlagenhauf P. The efficacy of repellents against Aedes, Anopheles, Culex and Ixodes spp. – a literature review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2013;11(6):374-411. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.10.005

- Fradin MS, Day JF. Comparative efficacy of insect repellents against mosquito bites. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(1):13-18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa011699

- Lengeler C. Insecticide-treated bed nets and curtains for preventing malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(2):CD000363. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000363.pub2

Other miscellaneous mentions and notes:

- Like textbook references?

- Mandell, Principles and Practice of ID, 8th Ed., 9th Ed.: Chapter 276 Malaria

- Comprehensive Review of Infectious Diseases

- AAP Red Book

Goal

Listeners will be able to diagnose and recommend management for severe malaria

Learning Objectives

After listening to this episode, listeners will be able to:

- Identify the necessary components of the history to gather for a patient presenting with fever and recent travel

- Describe the key diagnostics available malaria diagnosis

- Compare and contrast available antimalarials for chemoprophylaxis and treatment

Disclosures

Our guest (Christina Coyle) as well as Febrile podcast and hosts report no relevant financial disclosures

Citation

Coyle, C., Vasishta, S., Dong, S. “#47: Bad Air”. Febrile: A Cultured Podcast. https://player.captivate.fm/episode/0948e155-ec87-48a7-a08e-1cf07af6ef89