Table of Contents

Credits

Hosts: James Wilson, Sara Dong

Guest: Ryan Maves

Writing: James Wilson, Sara Dong

Producing/Editing/Cover Art/Infographics: Sara Dong

Our Guests

Dr. Ryan Maves is a Professor of Medicine and Anesthesiology at the Wake Forest School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where he serves as medical director of transplant infectious diseases and as a faculty intensivist at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center. A graduate of the University of Washington School of Medicine, he completed his internal medicine residency and fellowships in infectious diseases and critical care medicine at the Naval Medical Center in San Diego, California. Following fellowship, he served at the Naval Medical Research Unit No. 6 in Lima, Peru, leading studies in antimicrobial drug resistance and vaccine development. He returned to NMCSD in 2010, serving as ID division head. In 2012, Dr. Maves deployed to the NATO Role 3 Multinational Medical Unit at Kandahar Airfield, Afghanistan, as Director of Medical Services. After returning from deployment, he later served as vice chair of medicine and ID fellowship program director. He was the DoD coordinating principal investigator (PI) for the NIAID-sponsored Adaptive Covid-19 Treatment Trial (ACTT) and the San Diego site PI for the AstraZeneca/Oxford phase 3 ChAdOx1 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine trial. He retired from the United States Navy with the rank of Captain in 2021 after 22 years of active-duty service and joined the faculty at Wake Forest. Dr. Maves is board-certified in internal medicine, infectious diseases, and critical care medicine. He is the vice chair of the Fundamental Disaster Management committee in the Society of Critical Care Medicine and is the chair of the American College of Chest Physician’s Covid-19 Task Force. He lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Robin, and their three children. His research currently focuses on the epidemiology and treatment of severe viral diseases, including SARS-CoV-2, as well as disaster responses to public health emergencies.

Dr. James Wilson is an ID fellow at the combined Rush University Medical Center & Cook County Health ID fellowship program in Chicago, IL. He also spends time as an attending hospitalist at Rush as well. James is a Navy veteran physician of 10 years with aerospace and tropical medicine training through the US Department of Defense with several deployments into tropical and subtropical areas for global health, tropical medicine, and disaster relief.

Culture

Ryan shared Peacemaker, the HBO TV series

James shared some of Michael Lewis’ books (Liar’s Poker, Big Short, Flash Boys) and rock climbing

Consult Notes

Consult Q

Patient who presents after return from Thailand for fever and malaise

Case Summary

35 yo M who initially presented with fever and fatigue and was diagnosed with dengue. He returned several months later after another trip with retro-orbital pain, rash, and hypotension consistent with severe dengue.

Key Points

Check out the last episode Consult Notes for a summary of patient history questions you want to learn about for a febrile traveler

To complement this history section previously, here is a quick review of typical labs to obtain with fever and travel that both Ryan and Christina (in episode 47) mentioned:

- Routine lab tests:

- CBC with differential

- LFTs

- Blood cultures

- Urinalysis

- Blood smear for malaria (and rapid diagnostic test if available)

- A few others to consider based on history and exam

- Stool culture and/or examination for blood, ova¶sites

- Chest radiograph (+/- other imaging as needed)

- Serologies or other specific ID testing

- Biopsy of skin lesions, lymph nodes, etc if present

Here are some key resources mentioned on the show (plus a few others!)

- CDC Travelers’ Health Page and specific Destination pages

- CDC Yellow Book for health information for international travel

- Global TravEpiNet (GTEN) is a network of travel clinics across the US aimed at improving the health of those traveling internationally. They are supported by CDC

- Christina specifically mentioned Heading Home Healthy, which is a program supported by TravEpiNet, Mass General Hospital, and the CDC. Check out the interactive tool to guide travel counseling here!

- GeoSentinel is a worldwide communication and data collection network for surveillance of travel related morbidity (CDC supports; initiated by International Society of Travel Medicine)

- Travax provides info for travel health, but requires a subscription (your local travel clinic team might have access to this though)

- WHO International Travel and Health resources. Both the CDC and WHO websites are places to look for possible information on outbreaks as well

- Review articles:

- Thwaites GE, Day NP. Approach to Fever in the Returning Traveler. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(6):548-560. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1508435

- Ryan ET, Wilson ME, Kain KC. Illness after international travel. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(7):505-516. doi:10.1056/NEJMra020118

- Gautret P, Parola P, Wilson ME. Fever in Returned Travelers. Travel Medicine. 2019;495-504. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-54696-6.00056-2

- Fink D, Wani RS, Johnston V. Fever in the returning traveller. BMJ. 2018;360:j5773. Published 2018 Jan 25. doi:10.1136/bmj.j5773

- There are also comprehensive pages through UpToDate that you can reference as well that breaks down clinical approach by the syndrome, incubation period, exposure history and so on

Ryan pointed out a few overarching concepts when encountering a case of fever in a returning traveler. Here is a quick summary:

- In a returning traveler, there is an instinctive desire to reach for the geographically unique diseases that we don’t see commonly in North America – but it’s important to recognize that the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in returning travelers are cosmopolitan syndromes. It is important to consider a broad differential!

- Defining the range of relevant incubation periods will help limit the differential diagnosis

- Risks for infections in local residents and in visitors to a geographic region may differ

- “Malaria, rural, bites you at night. Aedes, urban, mosquitos bite you in the day”

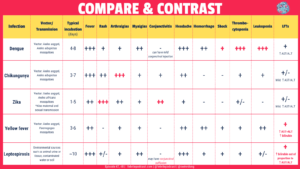

These Consult Notes will focus on dengue. Let’s start with a quick overview

- Dengue virus is a flavivirus. There are at least 4 serotypes (DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, DENV-4) – each serotype is antigenically distinct but related

- Vector = Aedes aegypti (principal vector) and Aedes albopictus mosquito, also known as Tiger mosquito (also the vector for chikungunya, yellow fever, and Zika viruses)

- After feeding on an infected person, the virus replicates in mosquito gut before disseminating to other tissues including salivary glands. This incubation period in the mosquito is about 8-12 days. Once infectious, mosquitos are capable of transmitting virus for rest of its life

- Dengue is present worldwide and year round in tropical and subtropical regions

- The serotypes can co-circulate within a region and many countries are hyper-endemic for all four serotypes

- Incubation period is 4-8 days [range 3-14 days]

- Resources:

A few notes about immune response and dengue

- Recovery from infection is believed to provide lifelong immunity against that serotype, but cross-immunity to other serotypes is only partial and temporary

- Antibody-dependent enhancement can occur, causing patients to develop higher immune responses with subsequent dengue virus exposure >> this leads to plasma leakage and progression to more severe forms of dengue

- Multiple studies have shown that the risk of severe disease is higher during a secondary DENV infection vs a primary infection

- Additional references:

- Halstead SB. Dengue Antibody-Dependent Enhancement: Knowns and Unknowns. Microbiol Spectr. 2014;2(6):10.1128/microbiolspec.AID-0022-2014. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.AID-0022-2014

- Anderson KB, Gibbons RV, Cummings DA, et al. A shorter time interval between first and second dengue infections is associated with protection from clinical illness in a school-based cohort in Thailand. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(3):360-368. doi:10.1093/infdis/jit436

- Montoya M, Gresh L, Mercado JC, et al. Symptomatic versus inapparent outcome in repeat dengue virus infections is influenced by the time interval between infections and study year. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(8):e2357. Published 2013 Aug 8. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002357

Dengue clinical presentation

- Diseases can range from a mild febrile illness to severe disease with shock and/or death

- Dengue causes a very wide spectrum of disease from subclinical to severe infection

- It typically will manifest as a flu-like illness with symptoms for 2-7 days. Symptoms include:

- Severe headache

- Retro-orbital pain

- Arthralgias, myalgias

- Nausea, vomiting

- Lymphadenopathy

- Rash

- The next section has a little bit more about the classification of dengue and specific definitions, but the main key is that dengue exists on a continuum of disease. As Ryan and James mentioned on the episode, clinicians must watch very closely for signs of vascular leakage around days 3-7 (danger period)

- Some classify dengue infection by phases: febrile phase > critical phase > convalescent phase.

- Labs you might expect would include: hypoalbuminemia, pancytopenia, LFT derangement, hemoconcentration

- You’ll find more about severe dengue/DHF/DSS below. It is important to note that this severe disease occurs in <1% of all infections

- Tourniquet test was mentioned on the show. This is performed by inflating a blood pressure cuff to halfway between systolic and diastolic pressure for ~5 minutes

- The test is positive if 10+ petechiae are counted per 2.5cm square

- This test can be negative or mildly positive during the phase of shock, and it usually becomes positive if conducted after recovery from shock

- As Ryan mentioned, this is an interesting physical exam tool but neither sensitive or specific for dengue diagnosis

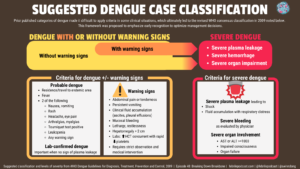

As discussed on the show, you may have previously heard the term “dengue hemorrhagic fever” rather than the newer terminology. Here is a quick overview of dengue classification

- Previously there was a division of dengue into: classic dengue, dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), dengue shock syndrome (DSS) [WHO 1997]

- They exist on a continuum but part of the difficulty was that DHF and dengue shock syndrome had fairly strict criteria. As Ryan discussed, patients with severe illness might not have met the criteria for DHF – but the term also suggested that hemorrhage was main manifestation when plasma leakage and shock was a more specific feature

- The WHO and other international groups moved away from that definition in ~2009

- The WHO classification now includes: dengue with or without warning signs, severe dengue [WHO 2009]

- These are still criticized as well, but have been adopted in many countries

- The revised 2009 classification includes:

- Dengue without warning signs:

- Presumptive diagnosis can be made:

- In setting of residence or travel to endemic area + fever + 2 of the symptoms below

- Nausea, vomiting, rash, myalgia, headache or eye pain, leukopenia, positive tourniquet test

- Presumptive diagnosis can be made:

- Dengue with warning signs:

- Diagnosis is made by above criteria + signs of endothelial damage/plasma leakage such as symptoms below

- Abdominal pain, thrombocytopenia, hemoconcentration, clinical fluid accumulation (edema/ascites, pleural effusions), hepatomegaly, bleeding, lethargy and persistent vomiting

- Severe dengue:

- Includes dengue infection with:

- Severe plasma leakage leading to shock or fluid accumulation with respiratory distress

- Severe bleeding

- Severe end-organ impairment: AST/ALT >=1000, impaired consciousness, organ failure

- This phase usually will be about 3-7 days after illness onset

- Includes dengue infection with:

- Dengue without warning signs:

- Some additional references:

- Srikiatkhachorn A, Gibbons RV, Green S, et al. Dengue hemorrhagic fever: the sensitivity and specificity of the world health organization definition for identification of severe cases of dengue in Thailand, 1994-2005. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(8):1135-1143. doi:10.1086/651268

- Srikiatkhachorn A, Rothman AL, Gibbons RV, et al. Dengue–how best to classify it. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(6):563-567. doi:10.1093/cid/cir451

- WHO Handbook for Clinical Management of Dengue [was released in 2012]

Dengue Diagnostics

- Diagnosis is often clinical, particularly in areas of high prevalence

- Can establish diagnosis directly by detecting viral components in serum in the first few days of infection

- Serum nonstructural protein (NS-1) antigen testing

- Blood PCR can detect viremia on day 1 of disease

- Urine PCR is probably more sensitive (as the period of viremia is relatively brief, but virus is shed in urine for longer stretch of time)

- Most people are viremic for about 4-5 days (but can last up to 12 days)

- Ryan also mentioned the Trioplex RT-PCR assay, which is assay that detects dengue, chikungunya, and Zika

- Serology

- Serology can be detected via ELISA

- IgM via ELISA will be detectable around 4-6 days after infection; remains detectable for about 3 months

- Significant cross-reactivity

- Paired acute and convalescent results demonstrating a 4fold rise in titers can be used

- Plaque reduction neutralization assays (PRNT)

- Incubates virus with serial dilutions of serum, then overlaid onto cell monolayer allowing virus to infect cells

- Look for viral cytopathic effect

- Noted 50% reduction in plaques compared to serum free virus is end point

- Useful for state DPH or CDC to ID specific virus

- Serology can be detected via ELISA

- Additional resources:

- Huits R, Soentjens P, Maniewski-Kelner U, et al. Clinical Utility of the Nonstructural 1 Antigen Rapid Diagnostic Test in the Management of Dengue in Returning Travelers With Fever. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(1):ofw273. Published 2017 Jan 9. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofw273

- Muller DA, Depelsenaire AC, Young PR. Clinical and Laboratory Diagnosis of Dengue Virus Infection. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(suppl_2):S89-S95. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw649

- Hunsperger EA, Muñoz-Jordán J, Beltran M, et al. Performance of Dengue Diagnostic Tests in a Single-Specimen Diagnostic Algorithm [published correction appears in J Infect Dis. 2017 Jun 1;215(11):1774]. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(6):836-844. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw103

- Guzman MG, Jaenisch T, Gaczkowski R, et al. Multi-country evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of two commercially-available NS1 ELISA assays for dengue diagnosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(8):e811. Published 2010 Aug 31. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000811

Dengue Management

- There is no specific treatment for dengue. The cornerstones of management rely on supportive care, frequent hemodynamic monitoring, and hydration

- There is no clear clinical trial data favoring a specific fluid therapy approach

- Initial crystalloid fluid resuscitation is appropriate. Colloid solution might be warranted for those with intractable shock

- Ryan and James addressed a few other items:

- NSAIDs are generally avoided given concern for effect on platelet function and potential risk of bleeding >> so acetaminophen is preferred

- Steroids don’t work

- There are no antiviral drugs available, although there are some under investigation. Given the effective agents against other important flaviviruses (namely Hepatitis C), there is hope for a direct viral inhibitor in the future

- Platelet transfusions have not been shown effective at preventing or controlled hemorrhage – but may be warranted in those with severe thrombocytopenia or active bleeding

- TNF-alpha inhibition has been used in animal studies in the past, but there is no clear human evidence – and this is likely not a scalable concept in most dengue endemic areas

- References:

- Lye DC, Archuleta S, Syed-Omar SF, et al. Prophylactic platelet transfusion plus supportive care versus supportive care alone in adults with dengue and thrombocytopenia: a multicentre, open-label, randomised, superiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10079):1611-1618. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30269-6

- Rajapakse S, de Silva NL, Weeratunga P, Rodrigo C, Fernando SD. Prophylactic and therapeutic interventions for bleeding in dengue: a systematic review. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2017;111(10):433-439. doi:10.1093/trstmh/trx079

- Zhang F, Kramer CV. Corticosteroids for dengue infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(7):CD003488. Published 2014 Jul 1. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003488.pub3

- Khan Assir MZ, Kamran U, Ahmad HI, et al. Effectiveness of platelet transfusion in dengue Fever: a randomized controlled trial. Transfus Med Hemother. 2013;40(5):362-368. doi:10.1159/000354837

- Tam DT, Ngoc TV, Tien NT, et al. Effects of short-course oral corticosteroid therapy in early dengue infection in Vietnamese patients: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(9):1216-1224. doi:10.1093/cid/cis655

- Lye DC, Lee VJ, Sun Y, Leo YS. Lack of efficacy of prophylactic platelet transfusion for severe thrombocytopenia in adults with acute uncomplicated dengue infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(9):1262-1265. doi:10.1086/597773

- Wills BA, Nguyen MD, Ha TL, et al. Comparison of three fluid solutions for resuscitation in dengue shock syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(9):877-889. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa044057

- Ngo NT, Cao XT, Kneen R, et al. Acute management of dengue shock syndrome: a randomized double-blind comparison of 4 intravenous fluid regimens in the first hour. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(2):204-213. doi:10.1086/318479

Dengue Prevention

- A few notes on dengue vaccination

- Ideally a dengue vaccine would produce protective immunity against all four DENV types (tetravalent immunity). We also would hope that vaccine protective immunity would be long-lived give the risk of severe disease in those with waning immunity

- The first dengue vaccine, CYD-TDV / Dengvaxia, was licensed in 2015 and is approved in ~20 countries

- Tetravalent chimeric vaccine

- Target population: people living in endemic area, 9-45 years old, at least 1 episode of prior dengue infection

- ACIP/US CDC recommended the vaccine for children aged 9-16 with serologic evidence of previous dengue infection and who live in endemic territories (Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Virgin Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Republic of Marshall Islands, Republic of Palau) in 2021

- As emphasized on the episode, the vaccine is NOT approved for travelers to dengue endemic areas and is not commercially available in the US

- To read more, here are the two RCTs with ~60% vaccine efficacy against virologically confirmed dengue; vaccine efficacy was higher for DHF or dengue requiring hospitalization

- Capeding MR, Tran NH, Hadinegoro SR, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of a novel tetravalent dengue vaccine in healthy children in Asia: a phase 3, randomised, observer-masked, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9951):1358-1365. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61060-6

- Villar L, Dayan GH, Arredondo-García JL, et al. Efficacy of a tetravalent dengue vaccine in children in Latin America. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(2):113-123. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1411037

- Re-analysis did show vaccine was protective against previously exposed children but there was increased risk of hospitalization and severe illness in those not previously exposed: Sridhar S, Luedtke A, Langevin E, et al. Effect of Dengue Serostatus on Dengue Vaccine Safety and Efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(4):327-340. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1800820

- There are several additional dengue vaccine candidates under evaluation

- Infection risk exists for anyone living or traveling in dengue-endemic region, but mosquito prevention is difficult. As Ryan mentioned in the show, Aedes aegypti are preferentially daytime feeders. Their feeding often is unnoticed and typical mosquito control measures (like bed nets) are not going to be useful for daytime feeders.

- Mosquito repellants and personal protection for mosquito bites are recommended for the primary prevention approach for travelers

- Counsel on how A.aegypti mosquitoes predominantly live in urban areas/near houses and are most active during daytime

- Screened or air conditioned buildings during the day

- If outside during the day, wear repellant and reduce amount of exposed skin

- Insecticide spraying has been used to reduce populations of mosquitoes but use in outbreaks has not been super effective. Ideally other approaches to mosquito control can be implemented (like reducing breeding sites)

- Mosquito repellants and personal protection for mosquito bites are recommended for the primary prevention approach for travelers

Other miscellaneous mentions and notes:

- Like textbook references?

- Mandell, Principles and Practice of ID, 8th Ed., 9th Ed.: Chapter 155: Flaviviruses

- Comprehensive Review of Infectious Diseases

- AAP Red Book

Goal

Listeners will be able to recognize dengue and understand factors involved in management and prevention

Learning Objectives

After listening to this episode, listeners will be able to:

- Identify the necessary components of the history to gather for a patient presenting with fever and recent travel

- Describe the diagnostics testing available for diagnosis of dengue

- Compare and contrast the clinical forms of dengue (dengue, dengue with warning signs, severe dengue)

Disclosures

Our guest (Ryan Maves) has a few disclosures:

- He is a co-owner of a patent on a dengue vaccine candidate that is not currently in clinical development

(unrelated to dengue/content on the episode):

- Research support (to institutions): AstraZeneca, AiCuris, Sound Pharmaceuticals, AlloVir

- Advisory panel membership: Trauma Insights LLC, EMD Serono

- Travel funding/honoraria: American College of Chest Physicians, Society of Critical Care Medicine

Febrile podcast and hosts report no relevant financial disclosures

Citation

Maves, R., Wilson, J., Dong, S. “#48: Breaking Down Breakbone”. Febrile: A Cultured Podcast. https://player.captivate.fm/episode/92eed283-e617-418a-ac7d-2163dce5cd18