Table of Contents

Credits

Hosts: Noah Rosenberg, Sara Dong

Guests: Nick Palmeri, Wendy Stead

Writing: Noah Rosenberg, Sara Dong

Producing/Editing/Cover Art/Infographics: Sara Dong

Our Guests

Guest Co-Host

Noah Rosenberg, MD

Dr. Rosenberg is a third year internal medicine resident at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston, MA.

Guest Discussant

Nick Palmeri, MD

Dr. Palmeri completed his Internal Medicine residency at Columbia, followed by Cardiology and Cardiac Electrophysiology fellowship at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, MA.

Guest Discussant

Wendy Stead, MD

Dr. Stead is the program director of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) Infectious Diseases Fellowship and an Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Stead completed her Internal Medicine residency and ID fellowship at BIDMC and then joined the BIDMC faculty with a joint appointment in the Divisions of Infectious Diseases and General Medicine and Primary Care in 2003. She also completed a Rabkin Fellowship in Medical Education in 2010. She dedicates herself to patient care, medical education, and curriculum development work at the residency and fellowship levels, winning many awards for teaching, mentorship, and humanistic care. Her active research interests include examining the effects of interdisciplinary education strategies on collaboration between specialty services, communication skills in patients with opioid use disorders, trainee wellness, and gender bias in academic medicine. She also loves narrative medicine and writing stories about her inspiring patients

Culture

Noah recently enjoyed going to a New England strawberry festival with his dog.

Nick recently traveled to Rhode Island and loves seeing his pug dog go swimming

Wendy has been listening to the podcast Slow Burn, based on prior american political scandals

Consult Notes

Case Summary

60 yo woman with HFrEF, DM2, CKD stage II, vfib arrest due to multivessel CAD s/p CABG, mitral valve repair, and ICD implantation 3 months prior to admission who developed purulent drainage from her ICD incision site.

Key Points

Cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs)

- Can include pacemakers (PPMs), implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs), and cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) devices with or without defibrillation (CRT-D or CRT-P)

- Additional novel devices have been developed and work without a transvenous or epicardial lead system:

- Leadless pacemakers are percutaneously placed directly inside the heart

- Subcutaneous ICDs and implantable loop recorders function effectively in an extrathoracic pocket without direct attachment to the heart

Epidemiology of CIED infections

- The true incidence is somewhat hard to define given there is no comprehensive registry or reporting system

- The rate of infections has ranged from about 0.8 – 5.7%, and it seems that increasing use of CIEDs has been associated with increased incidence of infection. Additionally, patients admitted for CIED infection experience significant mortality.

- Risk factors for CIED infection include:

- Manipulation of the device (such as newly implanted, device revision, or generator change)

- Number of prior procedures

- Immunocompromised state

- Renal dysfunction

- Postprocedure hematoma

- Device-related characteristics, such as epicardial leads or certain devices

- Nick discussed how there is some literature that ICDs and CRT have greater risk of infection than PPMs

- Olsen T, Jørgensen OD, Nielsen JC, Thøgersen AM, Philbert BT, Johansen JB. Incidence of device-related infection in 97 750 patients: clinical data from the complete Danish device-cohort (1982-2018). Eur Heart J. 2019;40(23):1862-1869. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz316

- Rattanawong P, Kewcharoen J, Mekraksakit P, et al. Device infections in implantable cardioverter defibrillators versus permanent pacemakers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2019;30(7):1053-1065. doi:10.1111/jce.13932

- The hope is that leadless pacemakers will have a lower risk of infection, although the data confirming this are lacking

- Nick discussed how there is some literature that ICDs and CRT have greater risk of infection than PPMs

- Among others

- Resources:

- Dai M, Cai C, Vaibhav V, et al. Trends of Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Device Infection in 3 Decades: A Population-Based Study. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2019;5(9):1071-1080. doi:10.1016/j.jacep.2019.06.016

- Greenspon AJ, Patel JD, Lau E, et al. 16-year trends in the infection burden for pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in the United States 1993 to 2008. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(10):1001-1006. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.04.033

- Khaloo P, Uzomah UA, Shaqdan A, et al. Outcomes of Patients Hospitalized With Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Device-Related Infective Endocarditis, Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis, and Native Valve Endocarditis: A Nationwide Study, 2003 to 2017. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(17):e025600. doi:10.1161/JAHA.122.025600

- Joy PS, Kumar G, Poole JE, London B, Olshansky B. Cardiac implantable electronic device infections: Who is at greatest risk?. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14(6):839-845. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.03.019

- Greenspon AJ, Eby EL, Petrilla AA, Sohail MR. Treatment patterns, costs, and mortality among Medicare beneficiaries with CIED infection. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;41(5):495-503. doi:10.1111/pace.13300

- Birnie DH, Wang J, Alings M, et al. Risk Factors for Infections Involving Cardiac Implanted Electronic Devices [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Feb 25;75(7):840-841] [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Aug 11;76(6):762]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(23):2845-2854. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.09.060

- Polyzos KA, Konstantelias AA, Falagas ME. Risk factors for cardiac implantable electronic device infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2015;17(5):767-777. doi:10.1093/europace/euv053

Microbiology of CIED infections

- Staph aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci cause the majority of generator pocket infections and device related endocarditis

- Other organisms could include:

- Streptococci

- Enterococci

- Corynebacterium spp

- Cutibacterium acnes

- Gram-negative bacilli

- Candida spp

- As Wendy mentioned, not all bacteremias are created equal in terms of the likelihood that they will involve a device.

- S.aureus bacteremia in patients with a CIED is associated with a relatively high rate of CIED infection, morbidity and mortality → important to carefully evaluate these patients with SAB for CIED infection

- Chamis AL, Peterson GE, Cabell CH, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in patients with permanent pacemakers or implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Circulation. 2001;104(9):1029-1033. doi:10.1161/hc3401.095097

- Uslan DZ, Dowsley TF, Sohail MR, et al. Cardiovascular implantable electronic device infection in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2010;33(4):407-413. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2009.02565.x

- Sohail MR, Palraj BR, Khalid S, et al. Predicting risk of endovascular device infection in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (PREDICT-SAB). Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8(1):137-144. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002199

- Coagulase-negative Staph and Enterococcus are other bacteremias that often prompt consideration of device infection

- We also discussed that Gram negative organisms seeding the CIED pocket/device are rare, although its possible

- Chesdachai S, Baddour LM, Sohail MR, et al. Risk of Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Device Infection in Patients Presenting With Gram-Negative Bacteremia. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(9):ofac444. Published 2022 Aug 25. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofac444

- Uslan DZ, Sohail MR, Friedman PA, et al. Frequency of permanent pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator infection in patients with gram-negative bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(6):731-736. doi:10.1086/506942

- S.aureus bacteremia in patients with a CIED is associated with a relatively high rate of CIED infection, morbidity and mortality → important to carefully evaluate these patients with SAB for CIED infection

Major CIED Guidelines/Statements

- American Heart Association (AHA) Update on CIED Infections and Their Management, 2010: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/circulationaha.109.192665

- Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) Expert Consensus Statement on CIED Lead Management and Extraction, 2017: https://www.hrsonline.org/guidance/clinical-resources/2017-hrs-expert-consensus-statement-cardiovascular-implantable-electronic-device-lead-management

- British (BSAC/BHRS/BCS/BHVS/BSE) Guidelines for CIED infection, 2014: https://bhrs.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/1501-Guidelines-for-the-Diagnosis-Prevention-and-Management-of-Cardiac-Implantable-Electronic-Device-Infection.pdf

- UpToDate Infections involving CIED Treatment & Prevention from Drs. Karchmer, Chu, Montgomery, last updated 3/2023: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/infections-involving-cardiac-implantable-electronic-devices-treatment-and-prevention?search=CIED&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~33&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) Consensus document, 2020: https://academic.oup.com/europace/article/22/4/515/5614580

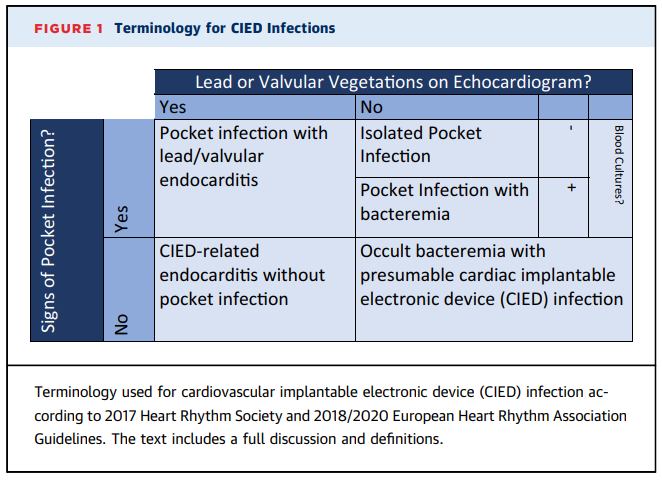

Defining CIED infections

- CIED infections are generally classified into categories of: pocket infection, systemic infection

- These categories are not mutually exclusive and can co-exist!

- You also may hear CIED infections classified as primary infection (when the device and/or pocket itself was source of infection) vs secondary (when leads or other components are seeded due to bacteremia from another source) → we’ll focus on the pocket vs systemic infection terminology here

- CIED pocket infection = infection involving the subcutaneous pocket containing the generator and the subcutaneous segment of the leads

- Patient generally have negative blood cultures and no evidence of lead/valve vegetation on transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE)

- Extension of pocket infection to involve intravascular lead(s) can occur, leading to systemic infection

- These infections are typically caused by skin flora / perioperative contamination, so often develop soon after implantation or a generator change – but pocket infections can occur with more chronic indolent infection as well

- Typically symptoms would include pocket discomfort, overlying erythema, swelling, and occasionally dehiscence / drainage from incision. Fever and systemic symptoms are often absence if just dealing wiht a localized pocket infection

- CIED systemic infection = infection involving the transvenous portion of the lead (with involvement of contiguous endocardium or tricuspid valve) or epicardial electrode (with involvement of epicardium)

- Can occur with or without generator pocket infection

- Generally have positive blood cultures and/or vegetation on TEE

- Infection primarily occurs on intracardiac portion of lead along the right atrium, tricuspid valve, or right ventricular contact point

- Seeding of CIED from bacteremia primarily involves the intracardiac lead and is caused most often by S.aureus

Imaging evaluation for CIED infection

- In addition to blood cultures of course!! We discussed imaging modalities for CIED infection during the episode

- All patients with suspected CIED infection should have echocardiogram performed (generally approach will be similar to endocarditis where you start with TTE with subsequent TEE if TTE is negative or additional evaluation is required)

- TEE is better than TTE for detecting lead and valve vegetations – but it cannot fully exclude CIED infection or endocarditis

- Nick and Wendy also spoke to the limitations of TEE for discriminating between infectious lead vegetations and thrombus or other non-infectious echodensities

- So when TTE/TEE is negative but intracardiac infection is still suspected, other imaging modalities might be considered:

- 18F-FDG-PET/CT scan. Here are 2 meta-analyses that showed high overall sensitivity/specificity for diagnosis of CIED infection, although this was higher for pocket/generator infection compared to lead-associated endocarditis

- Juneau D, Golfam M, Hazra S, et al. Positron Emission Tomography and Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography Imaging in the Diagnosis of Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(4):e005772. doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005772

- Mahmood M, Kendi AT, Farid S, et al. Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis of cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections: A meta-analysis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2019;26(3):958-970. doi:10.1007/s12350-017-1063-0

- Tagged WBC scan (scintigraphy and SPECT/CT)

- Cardiac CT angiography with or without EKG gating

- 18F-FDG-PET/CT scan. Here are 2 meta-analyses that showed high overall sensitivity/specificity for diagnosis of CIED infection, although this was higher for pocket/generator infection compared to lead-associated endocarditis

Management of CIED infections - Antibiotics

- CIED infections are managed with:

- Antibiotics

- Explantation of entire CIED (leads, including residual leads that are non-functional, and pulse generator)

- Reimplantation of a new device, if indication for CIED persists

- Antibiotic regimen will depend on the extent of infection and the organism identified

- Empiric antibiotic therapy should consist of antistaphylococcal treatment, which is often vancomycin

- If a patient is clinically stable, you may even consider holder antibiotics in anticipation of EP procedure if able

- Depending on patient history and instability, may consider Gram negative coverage as well

- Once organism is identified, the regimen can be tailored

- Empiric antibiotic therapy should consist of antistaphylococcal treatment, which is often vancomycin

- Duration of antibiotics

- No comparative trials in the current literature

- There is some variation in length of therapy recommended amongst the guidelines

- Pathogens isolated in cultures may determine the approach to therapy – again, variation amongst experts exists. Multidisciplinary team approach may be preferable in these cases

Treatment of CIED Infection: Duration of Antibiotics | ||||

Reference/ Guideline | Superficial infection (days) | Isolated pocket infection / Negative blood cultures (days) | Lead vegetation (weeks) | Valve vegetation (weeks) |

AHA, 2010 | 7-10 (PO) | Device erosion: 7-10 Inflammatory changes: 10-14 | Non-S.aureus: 2 S.aureus: 2-4 Complicated (ie septic venous thrombosis, osteomyelitis, etc): 4-6 | Treat as IE |

BSAC, 2015 | 7-10 (PO) | 10-14 | Treat as IE | Treat as IE |

HRS, 2017 | Not specified | 14 | Non-S.aureus: 2 S.aureus: 4 | Treat as IE |

EHRA, 2020 | 7-10 | 10-14 | 4 wks (but if follow-up blood cultures negative, clinical improvement without complication, treatment of 2 wks post-device extraction reasonable but total treatment duration of 4 wks) | Treat as IE |

Management of CIED infections - Explantation / Re-implantation

- Once you suspect a CIED infection, removal of the device is the most important management step

- Preferred approach for CIEd removal would be transvenous extraction of all leads (including previously abandoned leads if present) as well as removal of generator

- As Nick and Wendy discussed, this CIED removal may be trivial risk with recent implantations but often is more complicated with older devices that have been in place for a while

- Overall major complications of extraction are infrequent (<2%) and extraction related in-hospital mortality is <1%

- Ease of lead extraction is inversely related to lead dwell time (leads that have been in place more than 1-2 years are more difficult to extract than newer leads) → that said, even older leads can be removed safely by experienced docs in most cases

- Re-implantation recommendations vary between guidelines, but none recommend waiting for the full course of antibiotics to be completed

- The first step in this decision is to check on whether the device if needed. If the answer is no, then no need to re-implant!

- If yes, the recommendations by guidelines are noted below:

Re-implantation timing after CIED infection | |||

Reference/ Guideline | Positive blood cultures only and/or pocket infection only | CIED-lead infection | CIED-infective endocarditis |

AHA, 2010 | At least 72 hrs after 1st negative blood culture and adequate debridement of pocket if necessary | At least 72 hrs after 1st negative blood culture | 14 days post-CIED extraction and first negative blood culture – whichever comes later |

BSAC, 2015 | Resolution of signs/symptoms of infection and 7-10 days | ||

HRS, 2017 | At least 72 hrs after 1st negative blood culture | 3-14 days | |

EHRA, 2020 | Resolution of clinical signs/symptoms of infection and blood cultures negative for at least 72 hrs after extraction | ||

Additional resource:

Here is a review from one of our guests (and source of the terminology figure above): Palmeri NO, Kramer DB, Karchmer AW, Zimetbaum PJ. A Review of Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device Infections for the Practicing Electrophysiologist. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2021;7(6):811-824. doi:10.1016/j.jacep.2021.03.021

Infographics

Goal

Listeners will be able to discuss the microbiology, evaluation, and management of cardiac device infections

Learning Objectives

After listening to this episode, listeners will be able to:

- Identify the most common causative organism of CIED infections

- Compare and contrast the antimicrobial management of CIED pocket infection and systemic infections

- Discuss approach or guideline criteria to re-implantation of a device after CIED infection

Disclosures

Our guests as well as Febrile podcast and hosts report no relevant financial disclosures

Citation

Rosenberg, N., Palmeri, N., Stead, W., Dong, S. “#78: Achy Breaky Heart”. Febrile: A Cultured Podcast. https://player.captivate.fm/episode/f71eb1bc-8158-4dea-a5e3-01ae7c14ccfd