Credits

Host(s): Kevin He, Sara Dong

Guest: John Perfect

Writing: Kevin He, Kushal Vaishnani, Sara Dong

Producing/Editing/Cover Art/Infographics: Sara Dong

Our Guests

John R. Perfect, MD

John R. Perfect, MD is a James B Duke Professor of Medicine, Professor of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology, and Chief of Infectious Diseases at Duke University in North Carolina. His general research focus has been on cryptococcosis pathogenesis and management. He also investigates other fungal infections through translational and clinical trials and interacts as a consultant for many pharmaceutical companies in the antifungal space. Along with his basic science research, he also attends to patients at the beside. He is President of the Mycoses Study Group (MSG) based in USA and President-elect of the International Society of Human and Animal Mycology (ISHAM).

Kevin He, MD

Kevin is an internal medicine resident at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Kushal Vaishnani, MD

Dr. Kushal Vaishnani is a hospitalist in North Carolina with an interest in infectious diseases and clinical reasoning

Culture

Outside of spending time with his family, John shared his love for his profession and how he still enjoys coming to work to care for patients, do research, educate, and work with other faculty.

Consult Notes

Consult Q

Patient with HCV cirrhosis presenting with recurrent pleural effusions, consult for infectious work-up

One-liners

- 66 yo male with HCV cirrhosis found to have isolated pulmonary cryptococcal infection

- 35 yo male with HIV (not on ART) with cryptococcal meningitis

Key Points

Jump to:

John spoke about his differential diagnosis for this patient with a recurrent exudative pleural effusion. Here is a quick overview

- Typical bacterial pneumonia pathogens can certainly cause exudative pleural effusion, although the patient scenario’s pleural fluid suggested a more chronic process and less likely a bacterial infection (relatively low WBC counts, mostly mononuclear cells, negative gram stain)

- Tuberculosis

- Mycoses/fungal infections

- Histoplasma

- Cryptococcus

- Mucormycosis (more so in immunocompromised patients, those with neutropenia, etc)

- Coccidioides

- Others:

- Nocardia

- Actinomyces

- Parasitic (Paragonimus, T.solium, Chlonorchis, Echinococcus, Sparganum)

- Atypical pneumonia (viruses, mycoplasma)

- Extension from abscess elsewhere (hepatic/splenic/subphrenic)

- Spontaneous esophageal rupture

- Cholecystitis

- We focused here on ID causes, but there are certainly other non-infectious causes, such as malignancy, as well

Cryptococcosis Guidelines and Overview Resources:

- Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(3):291-322. doi:10.1086/649858

- Schelenz S, Barnes RA, Barton RC, et al. British Society for Medical Mycology best practice recommendations for the diagnosis of serious fungal diseases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(4):461-474. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70006-X

- Limper AH, Knox KS, Sarosi GA, et al. An official American Thoracic Society statement: Treatment of fungal infections in adult pulmonary and critical care patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(1):96-128. doi:10.1164/rccm.2008-740ST

- HIV-specific:

- A review paper on Cryptococcus from our guest: Maziarz EK, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30(1):179-206. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.006

Cryptococcus basics: microbiology & epidemiology

- 2 main spp: Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii

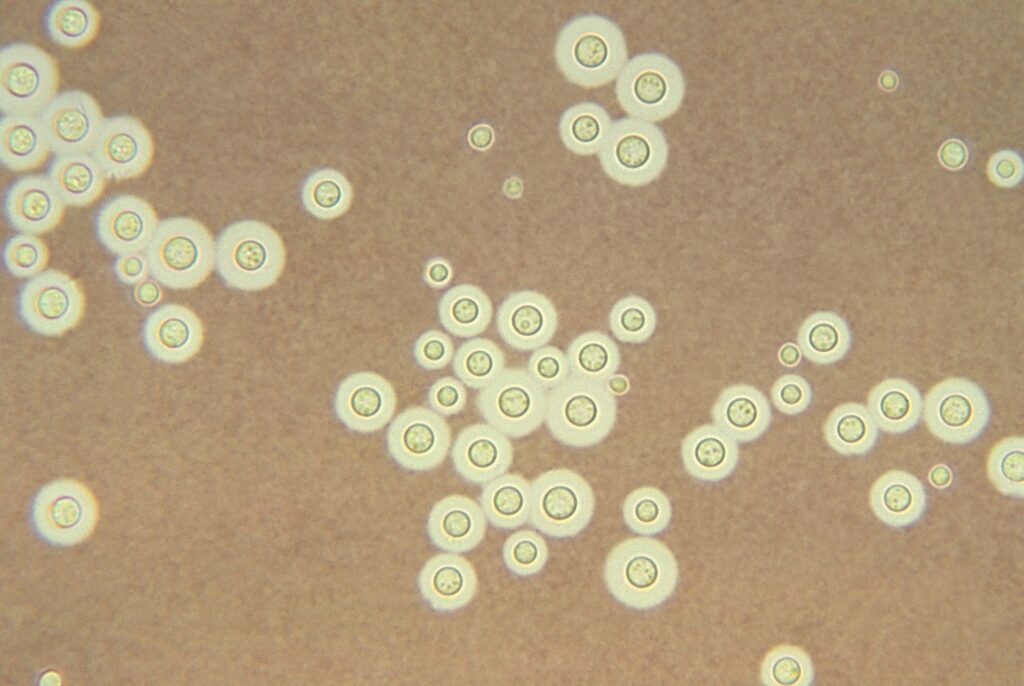

- Basidiomycetous, encapsulated yeasts with large polysaccharide capsule

- Life cycle has asexual and sexual forms. The asexual form exists as yeast, reproduces as simple narrow-based budding, and is the form of C.neoformans that has been recovered in human infections

Cryptococcus gattii

- Can manifest as potentially fatal meningoencephalitis and/or pulmonary disease

- Clusters in North America have largely been in British Columbia, Pacific Northwest; Otherwise found in tropical/subtropical regions such as Australia, Papua New Guinea

- Occasionally cases are noted in other areas even on East Coast, but only sporadic disease

- Although many clinical features of C.gattii are similar to C.neoformans, a few differences include:

- C.gattii more likely to cause large mass lesions (cryptococcomas) of lung or brain

- Largely affects immunocompetent patients (opposite of C.neoformans)

- Historically associated with eucalyptus trees, but has been noted in other deciduous trees and soil — **not associated with bird guano**

C.neoformans

- Worldwide distribution

- Most patients are immunocompromised (AIDS, prolonged glucocorticoids, organ transplant, malignancy, liver disease, sarcoidosis)

- C.neoformans has been found in soil and rotting vegetation from areas frequented by birds, especially pigeons, chickens, and turkeys

- We often hear of the classic association of pigeon guano with C.neoformans, but we know less about this link to birds than you might expect. Organisms are likely inhibited by pigeons’/birds/ high body temperature (so pigeons don’t become infected by C.neoformans in nature) — but yeast can be harbored in their GI tract

- As John mentioned, there is no established skin test for routine clinical use – so this reduces our ability to assess magnitude of infection – but many adults have specific Ab to C.neoformans Ag. He also briefly mentioned how a high percentage of pigeon breeders have been found to have cryptococcal Ab in the past. Here are two older papers:

- Ab against cryptococcus were found in 10/50 asymptomatic breeders, 5/6 with pigeon breeders’ disease, and all 5 with cryptococcosis — Fink JN, Barboriak JJ, Kaufman L. Cryptococcal antibodies in pigeon breeders’ disease. J Allergy. 1968;41(5):297-301. doi:10.1016/0021-8707(68)90035-x

- ~22% of pigeon breeders were positive for Cryptococcus Ab compared to 3% in control group: Walter JE, Atchison RW. Epidemiological and immunological studies of Cryptococcus neoformans. J Bacteriol. 1966;92(1):82-87. doi:10.1128/jb.92.1.82-87.1966

- As John mentioned, there is no established skin test for routine clinical use – so this reduces our ability to assess magnitude of infection – but many adults have specific Ab to C.neoformans Ag. He also briefly mentioned how a high percentage of pigeon breeders have been found to have cryptococcal Ab in the past. Here are two older papers:

- Outbreaks haven’t really been traced to pigeon roosting areas, although the fungus is isolated from those areas.

- Most patients are immunocompromised — Risk factors for disease include: HIV/AIDS, corticosteroid therapy, organ transplant, lymphoproliferative disorders, monoclonal Ab use (infliximab, adalimumab, alemtuzumab), sarcoidosis, autoantibodies to GM-CSF, idiopathic CD4 lymphocytopenia (CMI), hyperIgM or hyperIgE syndrome, cirrhosis

Pathophysiology

- Inhale basidiospore form of fungus or small poorly encapsulated yeasts, which then deposit in alveoli and terminal bronchioles

- Likely causes focal pneumonitis that may or may not be symptomatic

- Alveolar macrophages recruit other inflammatory cells and elicit Th1 response/granulomatous inflammation

- Infection might be cleared by some hosts

- John also spoke about how there can be pulmonary foci/granulomas and thoracic lymph nodes containing cryptococcus yeasts. Crypto sits in the lymph node complex and infection can persist in latent state, similar to TB or Histoplasma

- A pearl from John: Cryptococcus in sitting in lymph node is similar to TB and Histoplasma. In contrast — In TB, can see Ghon complex, whereas Crypto focus is much smaller. Histoplasma loves to calcify, which Crypto does not typically do.

- Later on, if the host becomes immunocompromised, organisms may cause reactivation disease from the granulomatous complexes

- Primary infection in a naive host or reinfection with new strain is possible, but typically ICH cases are reactivation of latent infection

- Pathogenesis of cryptococcosis is determined by (1) host defense status (2) virulence of specific Cryptococcus strain (3) size of inoculum

- Virulence factors to remember:

- Antiphagocytic polysaccharide capsule formation

- Melanin pigment production which helps protect against oxidative stresses

- Thermotolerance – the “yeast that likes it hot”

Clinical manifestations: Cryptococcus most commonly affects the lung and central nervous system (CNS)

- Cryptococcal lung disease

- Can range from asymptomatic to single pulmonary nodule to acute life-threatening pneumonia

- Abnormalities on chest imaging can be variable – as John mentioned, it can really be anything!

- Nodules, lymphadenopathy, lobar or interstitial infiltrates, cavities, etc

- Can occasionally occur with co-infection

- Serum CrAg is often negative in true isolated pulmonary cryptococcosis

- CNS cryptococcal disease: A critical feature is the propensity for CNS complications

- Cryptococcal meningoencephalitis (acute, subacute, chronic)

- Classic signs like fever, meningismus, and photophobia are present in only ~⅓ of patients, so the clinical signs can be unreliable

- Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) and neuroinvasion leads to encephalopathic symptoms.

- Later on in course can also have cranial nerve palsies. Ocular nerve involvement in particular is common

- Cerebral cryptococcomas (seen more with C.gattii)

- Spinal cord granuloma

- Cryptococcal meningoencephalitis (acute, subacute, chronic)

- Cryptococcal cutaneous disease

- Large variability in possible appearances, but classic = papules with central umbilication, resembling molluscum contagiosum

- Most cases of skin lesions represent disseminated disease, although direct inoculation is possible

- Other less common disease manifestations:

- Remember eye involvement (noted above as well), such as papilledema, keratitis, endophthalmitis

- Prostatic infection (can serve as important reservoir for disease relapse)

- Osteoarticular (vertebral osteomyelitis most commonly)

- Peritonitis

A few other pearls from John

A major branch point in thinking about clinical manifestations is whether the infection has spread. If you see CrAg in blood, it likely suggests that it has “left the house” as John said and went elsewhere out of the lung. “It worries me more than I can precisely tell you”

A huge risk factor for doing poorly with cryptococcosis is a patient with severe liver disease who gets disseminated crypto. It can also be hard to identify this given a patient with cirrhosis may not produce as much fever or have a delayed diagnosis due to anchoring on hepatic encephalopathy as cause of change in mental status.

Diagnosis: Definitive diagnosis can be made in a few different ways.

Direct examination

- India ink preparation of CSF and direct microscopic examination for encapsulated yeasts can be used where available (but this is less common in many places now with CrAg testing). Sensitivity depends on fungal burden, and false positive might result from intact lymphocytes, other cells, or nonviable yeast forms

Culture

- Cryptococcus can be readily cultured from CSF, sputum, and biopsy on routine fungal and bacterial culture media

- Usually observed after 48-72h with white/cream colored colonies that may be more orange or brown after prolonged incubation

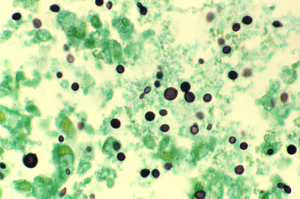

- Micro pearl: concanavalin-glycine-thymol agar turns blue for C.gattii but not C.neoformans

Cytology and Histopathology

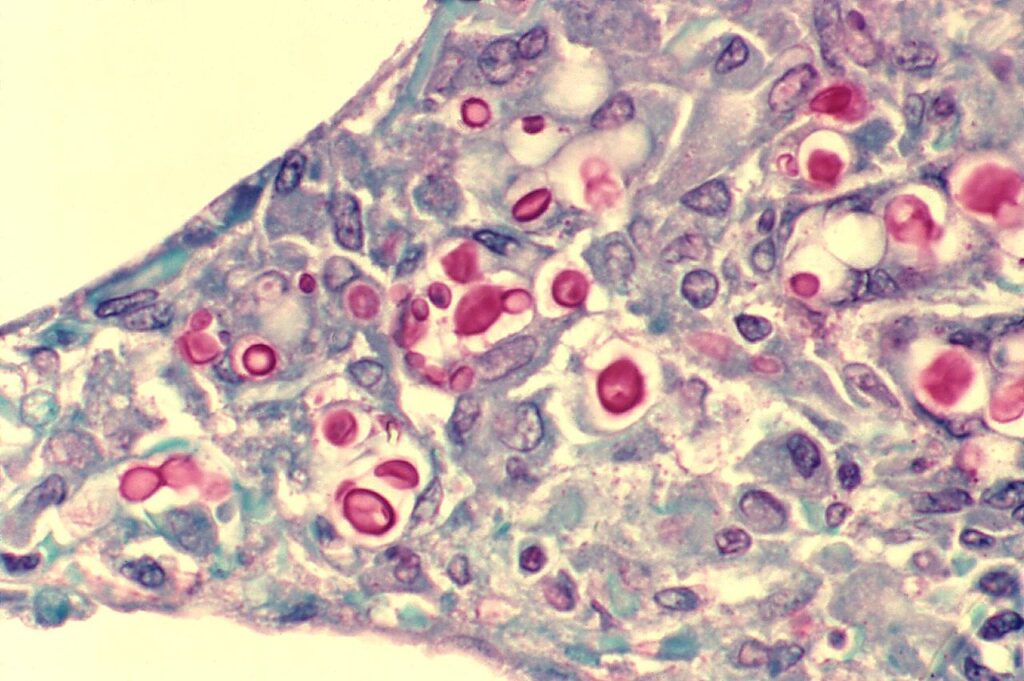

- Can identify with staining of tissues from lung, skin, brain, etc → yeast that reproduces by narrow based budding

- H&E: 4-10 um yeasts, large clearing from capsule that doesn’t stain

- Special stains that label the polysaccharide capsule:

- Mucicarmine: stains capsule pink or red color

- Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)

- Alcian blue: stain capsule blue

- Fontana-Masson stain identifies melanin in yeast cell wall

- Other fungal stains can stain cell wall, such as Calcofluor or Gomori methenamine silver (GMS)

Cryptococcal Ag (CrAg)

- Diagnosis was improved significantly with tests for cryptococcal polysaccharide capsular antigen (CrAg), which can be performed on serum or CSF

- The lateral flow assay (LFA) is preferred over other methods (latex agglutination, enzyme immunoassay) given rapid turnaround, higher sensitivity/specificity, lower cost, minimal requirements for lab infrastructure

- Baseline CrAg titers in serum and CSF correlate with fungal burden and carry prognostic significance in cryptococcal meningitis

- *There is no role for monitoring serum CrAg titers to determine duration of therapy in either immunosuppressed or immunocompetent hosts*

- The kinetics of antigen clearance are slower and less predictable markers of treatment response (compared to culture)

- Different labs also might be using different testing, so difficult to compare Ag titers across labs

- FP CrAg: Trichosporon asahii or Stomatococcus or Capnocytophaga

- FN CrAg: large amount of Ag (prozone phenom) if lab is using latex agglutination and doesn’t pretreat

CSF testing

- A quick note on expected CSF profile with meningitis: would expect elevated opening pressure, mildly elevated protein, low to normal glucose, lymphocytic pleocytosis

So who needs an LP?

- Dissemination from lungs to CNS in immunocompetent patients is rare –> so routine LP to evaluate for cryptococcal meningoencephalitis is not necessary in asymptomatic immunocompetent hosts with CrAg <1:512

- LP should be obtained for any patients with:

- Neurologic symptoms

- Immunocompromised hosts and those with underlying condition that predisposes to disseminated disease

- Would also consider if very high serum CrAg titer (>=1:152) given likely higher burden with risk for extrapulmonary spread and a poor prognostic factor

Classification of Disease & Management

- Basic principles

- Treatment approach is larged based on and extrapolated from management of patients with HIV infection and CNS cryptococcal disease

- An asymptomatic immunocompetent patient diagnosed incidentally in setting of a pulmonary nodule to rule out malignancy (with negative culture, negative CrAg) may not need therapy

- An asymptomatic patient with a detectable serum CrAg probably has low likelihood of systemic dissemination, but treatment with fluconazole is appropriate — because it is curative and risk of adverse event is low

- Immunocompetent patients with mild to moderate localized pulmonary cryptococcosis

- Fluconazole 400mg for 6-12 months

- Severe pulmonary disease, disseminated infection (at least 2 noncontiguous sites of infection), or those with CrAg >=1:152 (known poor prognostic factor) is managed with 3 phases of treatment

- Induction

- Liposomal amphotericin (Ambisome) + Flucytosine for at least 2 wks

- Some patients might need extension to 4-6 weeks, depending on the presence of serious neurologic complications, radiographic evidence of brain involvement (cryptococcomas), underlying conditions, response to therapy

- Ampho B deoxycholate was cornerstone, but most are using liposomal AmB as preferred alternative given similar outcomes and less nephrotoxicity

- Repeat LP after 2 wks → Cultures should be negative at end of 2 wks. The delay while awaiting culture results can make transition to consolidation phase difficult, so can also consider prognostic factors:

- Transition if anticipate negative cultures based on clinical response to treatment and favorable baseline CSF studies — but otherwise likely would wait on cultures

- If culture returns positive, reinitiate or continue induction therapy with serial LPs every 2 wks until CSF sterile

- Liposomal amphotericin (Ambisome) + Flucytosine for at least 2 wks

- Amphotericin + Flucytosine is the most potent regimen, with faster CSF sterilization, improved survival, and fewer relapse.

- If unable to use flucytosine, use of Fluconazole + AmB is still better than AmB alone

- Induction

- Consolidation

- Fluconazole 400-800mg for 8 weeks

- Many experts, including our guest, favor higher dose of Fluc (800mg)

- 8 weeks

- Maintenance/Suppression

- Fluconazole 200-400mg daily for generally one year

- High percentage of relapse would happen in the first year, which is why this phase is used to extend therapy. If patients remain on high doses of immunosuppression or still have radiographic cryptococcomas, would adjust this duration on case-by-case basis

- A few notes on medications and adverse effects to remember

- Amphotericin:

- Electrolyte disturbances, anemia, renal insufficiency, infusion site reaction (these are reduced with liposomal preparation)

- Flucytosine (5FC):

- Limited available in setting where disease burden and mortality is high

- Adverse effects: cytopenias, hepatotoxicity, GI intolerance

- Fluconazole:

- Generally well tolerated but may have rash or abnormal transaminases

- Adjust dosing for renal dysfunction

- Watch for drug-drug interactions (azoles, CNI, or sirolimus)

- Other azoles (itra/vori/posa/isav) are possible alternatives to fluconazole but there is minimal data on their use in this setting

- Antifungal drug resistance is uncommon

- Amphotericin:

- Other management:

- Intracranial pressure control is a critical determinant of outcome for cryptococcal meningoencephalitis

- If pressure >=25 and symptoms of increased ICP during induction — CSF drainage should be performed to reduce pressure by 50% (if extremely high) or to nl pressure <=20

- Therapeutic LP daily in setting of clinical symptoms and persistent pressure >=25 until stabilized for 2 days

- Temporary percutaneous lumbar drains or ventriculostomy may be appropriate. In certain cases, VP shunt may be warranted as well

- Do not use mannitol or acetazolamide

- Modulating immunosuppression as able

- Intracranial pressure control is a critical determinant of outcome for cryptococcal meningoencephalitis

- We won’t get into persistent or relapsed infection here, but a brief note on risk factors for relapse:

- Low initial CSF wbc

- Persistently low CSF glucose after 4 wks of therapy

- Treatment with prednisone >=20mg or equivalent that continues after completion of AF therapy

- Diamond RD, Bennett JE. Prognostic factors in cryptococcal meningitis. A study in 111 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1974;80(2):176-181. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-80-2-176

- Mourad A, Perfect JR. Present and Future Therapy of Cryptococcus Infections. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4(3):79. Published 2018 Jul 3. doi:10.3390/jof4030079

John discussed CrAg screening in asymptomatic patients with HIV

- If the screening CrAg is positive and there are symptoms, certainly would get an LP

- If the screening CrAg is positive and the patient is asymptomatic, they should get an LP as well

- There is ongoing research about what to do with CrAg+ patients with HIV, particularly looking at titers, and what to do when there is a negative LP

- In the DHHS HIV guidelines, Serum CrAg screening is recommended for asymptomatic patients with HIV and CD4 count <=100 who are not on effective ART

- There may be benefit to screen at higher CD4 count thresholds in certain areas of high prevalence for cryptococcal disease, and certain countries have adopted screening at different CD4 counts

- Ford N, Shubber Z, Jarvis JN, et al. CD4 Cell Count Threshold for Cryptococcal Antigen Screening of HIV-Infected Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(suppl_2):S152-S159. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1143

- Mfinanga S, Chanda D, Kivuyo SL, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis screening and community-based early adherence support in people with advanced HIV infection starting antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania and Zambia: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9983):2173-2182. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60164-7

- Universal prophylaxis though is generally not recommended: relatively cost ineffective, hasn’t been shown to offer overall survival benefit, and may contribute to azole-resistance strains.

- …but there are studies in resource-limited settings with a high prevalence of disease that suggest benefit to strategy of screening and pre-emptive antifungal therapy (to prevent meningitis)

- Longley N, Jarvis JN, Meintjes G, et al. Cryptococcal Antigen Screening in Patients Initiating ART in South Africa: A Prospective Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(5):581-587. doi:10.1093/cid/civ936

- Li Y, Huang X, Chen H, et al. The prevalence of cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) and benefits of pre-emptive antifungal treatment among HIV-infected persons with CD4+ T-cell counts < 200 cells/μL: evidence based on a meta-analysis [published correction appears in BMC Infect Dis. 2021 Jun 24;21(1):604]. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):410. Published 2020 Jun 12. doi:10.1186/s12879-020-05126-z

- Mfinanga S, Chanda D, Kivuyo SL, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis screening and community-based early adherence support in people with advanced HIV infection starting antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania and Zambia: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9983):2173-2182. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60164-7

- Temfack E, Bigna JJ, Luma HN, et al. Impact of Routine Cryptococcal Antigen Screening and Targeted Preemptive Fluconazole Therapy in Antiretroviral-naive Human Immunodeficiency Virus-infected Adults With CD4 Cell Counts <100/μL: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(4):688-698. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy567

- Chetchotisakd P, Sungkanuparph S, Thinkhamrop B, Mootsikapun P, Boonyaprawit P. A multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of primary cryptococcal meningitis prophylaxis in HIV-infected patients with severe immune deficiency. HIV Med. 2004;5(3):140-143. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1293.2004.00201.x

We have discussed conditions to potentially delay initiation of ART therapy in our HIV series: cryptococcal meningitis and TB meningitis given risk of IRIS (immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome). How long do we wait after starting antifungal therapy to start ART?

- The timing of ART initiation is trying to weight advantage of early immune recovery against the risk of IRIS

- For patients with cryptococcal meningoencephalitis, guidelines recommend starting ART 2-10 weeks after antifungal therapy has been started. When to initiate in that 2-10 week window is not quite as clear

- Trials comparing early vs delayed initiation of ART in patients with CM consistently show improved survival with delayed initiation

- A key paper showing the benefit of delayed ART is the COAT trial (Cryptococcal Optimal ART Timing Trial): Boulware DR, Meya DB, Muzoora C, et al. Timing of antiretroviral therapy after diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(26):2487-2498. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1312884

- 177 pts with HIV from Uganda and South Africa

- Assigned to either early ART within 1-2 wks after initiating antifungals vs. delayed ART (4-6 weeks after initiating therapy)

- Mortality at 26 weeks was significantly higher in patients with early ART compared to delayed (45% vs 30%)

- Other papers:

- Makadzange AT, Ndhlovu CE, Takarinda K, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of antiretroviral therapy for concurrent HIV infection and cryptococcal meningitis in sub-saharan Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(11):1532-1538. doi:10.1086/652652

- Bisson GP, Molefi M, Bellamy S, et al. Early versus delayed antiretroviral therapy and cerebrospinal fluid fungal clearance in adults with HIV and cryptococcal meningitis [published correction appears in Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Oct;57(7):1067]. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1165-1173. doi:10.1093/cid/cit019

Other miscellaneous mentions and notes:

- Like textbook references?

- Mandell, Principles and Practice of ID, 8th Ed., 9th Ed.: Chapter 264 Cryptococcosis

- Long, Principles and Practice of Pediatric ID, 5th Ed.: Chapter 249 Cryptococcus Species

- Comprehensive Review of Infectious Diseases

- AAP Red Book

- John emphasized the “Goldilocks” paradigm for the immune state and cryptococcus: Too much or too little immune response to cryptococcus can lead to disease. You can read a little more about this paper, where John uses cryptococcosis as a model for understanding infectious diseases.

- Not totally related to the episode, but just a nice paper on combination antifungal therapy that our guest was an author on: Johnson MD, MacDougall C, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Perfect JR, Rex JH. Combination antifungal therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(3):693-715. doi:10.1128/AAC.48.3.693-715.2004

- A few other papers from John Perfect with excellent titles that I just have to share:

Episode Art & Infographics

Goal

Listeners will be able to describe the clinical presentation and management of cryptococcosis.

Learning Objectives

After listening to this episode, listeners will be able to:

- Discuss the differential diagnosis of recurrent pleural effusion

- Identify the two most common cryptococcal species and describe their relevant epidemiology and pathophysiology

- Compare and contrast isolated pulmonary cryptococcosis to disseminated disease

- Define the indications for lumbar puncture in setting of suspected or confirmed cryptococcal infection

Disclosures

Febrile podcast and hosts report no relevant financial disclosures

Citation

Perfect, J., He, K., Dong, S. “#17: Yeastie Boys”. Febrile: A Cultured Podcast. https://player.captivate.fm/episode/8eacc591-95d2-4838-bb56-49fc67ed97b3

2 thoughts on “Episode #17 – Yeastie Boys”

OMG! A Perfect episode!

Greetings from Spain, I’m a huge fan of Febrile!

Fast question. Should I screen potential solid organ transplant recipients with CrAg?

Hi! Thanks for your patience and not getting to this question earlier! As far as I know, CrAg screening of transplant recipients or their donors in general is not recommended (as we generally wouldn’t give them any antifungal prophylaxis for crypto either)

Comments are closed.