Credits

Host(s): Lea Goren, Alice Lehman, Sara Dong

Guest: Beth Thielen

Writing: Lea Goren, Alice Lehman, Beth Thielen, Sara Dong

Producing/Editing/Cover Art: Sara Dong

Infographics: Lea Goren, Alice Lehman, Beth Thielen

Our Guests

Beth Thielen, MD, PhD

Dr. Beth Thielen is an adult and pediatric infectious disease physician at University of Minnesota and leads a translational research lab studying interactions between the human host immune system, respiratory viral pathogens and the respiratory microbiota. She completed her MD/PhD training at University of Washington where she performed dissertation research on HIV pathogenesis in the Department of Global Health. She then returned to Minnesota for both her med-peds residency and med-peds ID fellowship, where she acquired skills in molecular epidemiology at the Minnesota Department of Health and mouse models of influenza pathogenesis with Dr. Ryan Langlois (Lang-loy). In addition to her interests in respiratory viral pathogenesis, she also has clinical interests in other infections of immunocompromised patients, travel and tropical medicine. and clinical immunology and the role that host genetic variation plays in the response to infectious diseases.

Check out her lab website here

Culture

We were lucky to get several recommendations this week!

For understanding where your patients come from, Beth recommended City of Thorns by Ben Rawlence, which has the stories of nine individuals from inside the Dadaab refugee camp in northern Kenya.

For taking the time to think about sustainability in medicine and happiness, Beth mentioned The Happiness Lab and Ten Percent Happier podcasts.

For true crime fans, Beth recommended the Bear Brook podcast which uses genetic genealogy to solve crimes.

Consult Notes

Consult Q

What testing and treatment should we implement for a patient with a lytic bone lesion found to have granulomatous inflammation on pathology?

One-liner

2-year-old immigrant child from East Africa presenting with a lytic bone lesion who was found to have BCG osteomyelitis

Key Notes

Jump to:

This episode discussed the ID differential for granulomatous inflammation in bone or soft tissue, which included:

- Mycobacterial disease (TB, NTM, leprosy)

- Bartonella

- Endemic mycoses (Blastomyces >> Histoplasma if involving bone)

- Brucella

- Syphilis

- Coxiella

Ddx also includes non-infectious etiologies such as sarcoidosis, autoimmune disease, or possible malignancy.

Alice and Beth also discussed the differential diagnosis for radiolucent or lytic bone lesions:

- Infection/osteomyelitis

- Staph aureus

- Kingella kingae

- Group A Strep

- Strep pneumoniae

- H.influenzae

- Salmonella

- Histoplasma

- Blastomyces

- M.tuberculosis

- Neoplastic

- Histiocytic process, such as Langerhans cell histiocytosis or eosinophilic granuloma

- Hyperparathyroidism (browns tumor)

- Unicameral bone cyst

- Benign lesions:

- Fibrous dysplasia

- Enchondroma

- Non-ossifying fibroma

- Osteoblastoma

- Chondroblastoma

- Primary malignant tumors, such as osteosarcoma, or metastases

What are appropriate infection control precautions for suspected pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB?

- Most are familiar with the need for airborne precautions for suspected pulmonary TB

- Airborne precautions are only required for extrapulmonary disease if there is risk of aerosolizing infected material from the extrapulmonary site. This might include:

- Draining open wound or abscess with high concentration of organisms

- Surgical procedure or drainage of fluid where drilling into bone is performed. In certain settings, I&D may only be sampling/curettage, which is not considered an aerosolizing situation

- Disease in oral cavity or larynx

- A key point though is that persons with extrapulmonary TB disease may have concomitant pulmonary disease, which would require precautions!!!

- It is also worth noting that children under the age of about 8 have a lower risk for transmitting pulmonary TB

So in summary, extrapulmonary TB is usually not a risk for transmission except with:

- Concomitant pulmonary TB

- Oral cavity or laryngeal TB

- Open abscess or lesion with high concentration of organisms and extensive drainage – or if aerosolization of drainage fluid is performed

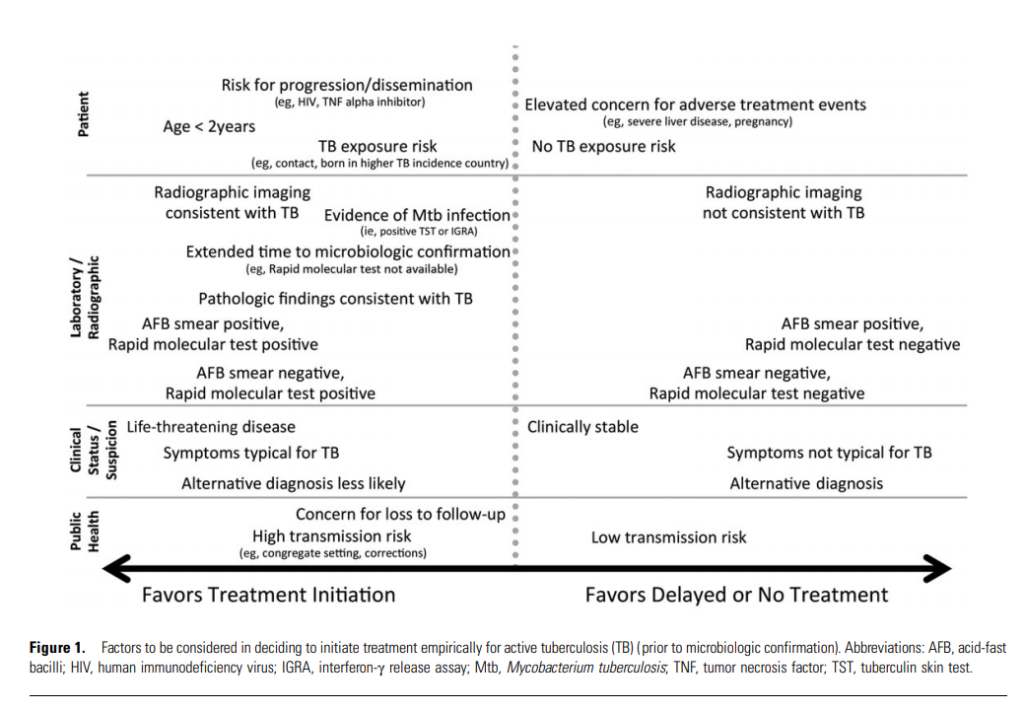

The ATS/CDC/IDSA tuberculosis treatment guidelines offer a framework for thinking about factors that favor empiric treatment for active TB. A few of those risks that we discussed are noted in the bullets below, but you can see the full figure underneath that.

- Risk for progression including age <2 years old

- Evidence of MTB infection (IGRA or TST results)

- Pathologic findings consistent with TB

- Symptoms typical for TB

- Lack of alternative diagnosis

- Concern for loss to follow-up

Experts favor the use of IGRAs in children down to age 2, especially in the setting of BCG vaccination. There have been various studies and analyses that have demonstrated IGRAs perform well in these age ranges, check out these:

- Kay AW, Islam SM, Wendorf K, Westenhouse J, Barry PM. Interferon-γ Release Assay Performance for Tuberculosis in Childhood. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6):e20173918. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-3918

- Stout JE, Wu Y, Ho CS, et al. Evaluating latent tuberculosis infection diagnostics using latent class analysis. Thorax. 2018;73(11):1062-1070. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211715

- Velasco-Arnaiz E, Soriano-Arandes A, Latorre I, et al. Performance of Tuberculin Skin Tests and Interferon-γ Release Assays in Children Younger Than 5 Years. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37(12):1235-1241. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000002015

- Ahmed A, Feng PI, Gaensbauer JT, et al. Interferon-γ Release Assays in Children <15 Years of Age [published correction appears in Pediatrics. 2020 May;145(5):]. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1):e20191930. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-1930

A few other TB resources to save:

- Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, et al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(2):111-115. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw778

- Nahid P, Mase SR, Migliori GB, et al. Treatment of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. An Official ATS/CDC/ERS/IDSA Clinical Practice Guideline [published correction appears in Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Feb 15;201(4):500-501]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(10):e93-e142. doi:10.1164/rccm.201909-1874ST

- Sterling TR, Njie G, Zenner D, et al. Guidelines for the Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: Recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69(1):1-11. Published 2020 Feb 14. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6901a1

What is BCG?

- Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) immunization against tuberculosis >> this is a group of related live vaccines derived from attenuated Mycobacterium bovis

- The BCG vaccine is used in >100 countries and the most widely administered vaccine in the world. Given as dose intradermally into the deltoid muscle

- There are various BCG vaccines used throughout the world which differ in composition and efficacy

- The BCG vaccine is given to reduce the incidence of disseminated and other life-threatening manifestations of TB in infants and young children

- Prior meta-analyses or published clinical trials and case-control studies concerning the efficacy of BCG vaccines concluded that BCG vaccine has relatively high protective efficacy (~80%) against meningeal and miliary TB in children

- It is poorly protective against pulmonary disease in adolescents and adults

- Of note, BCG has been associated with overall reduction in childhood mortality not attributable to TB, but this effect is not really understood

- BCG is generally not recommended for use in the US given low risk of MTB infection in general population

Links:

- Colditz GA, Brewer TF, Berkey CS, et al. Efficacy of BCG vaccine in the prevention of tuberculosis. Meta-analysis of the published literature. JAMA. 1994;271(9):698-702.

- Colditz GA, Berkey CS, Mosteller F, et al. The efficacy of bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccination of newborns and infants in the prevention of tuberculosis: meta-analyses of the published literature. Pediatrics. 1995;96(1 Pt 1):29-35.

- Rodrigues LC, Diwan VK, Wheeler JG. Protective effect of BCG against tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis: a meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22(6):1154-1158. doi:10.1093/ije/22.6.1154

- Trunz BB, Fine P, Dye C. Effect of BCG vaccination on childhood tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis worldwide: a meta-analysis and assessment of cost-effectiveness. Lancet. 2006;367(9517):1173-1180. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68507-3

- WHO Report on BCG vaccine use for protection against mycobacterial infections including tuberculosis, leprosy, and other nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) infections

BCG Clinical Pearls:

- Check out the BCG World Atlas to quickly see BCG vaccination policies by country as well as other information such as TB incidence

- Pyrazinamide resistance can be a clue that you are dealing with M. bovis.

Beth discussed in the show about Quantiferon vs TB PCR in detection of BCG. Here is an overview of interpreting TST and IGRA after BCG!

- Most who receive BCG vaccine have TST reaction 2-3 mo following vaccination. This often wanes with time and can be <10mm after 10+years from vaccination → but reactions can be boosted and childhood BCG vaccine has variable effects on TST in adulthood

- This study showed 8% had +TST 10-25y after BCG: Menzies R, Vissandjee B. Effect of bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination on tuberculin reactivity. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145(3):621-625. doi:10.1164/ajrccm/145.3.621

- In this long-term follow-up in the US, individual with BCG vaccine after infancy had TST reactions >=10mm for as long as 55 years: Mancuso JD, Mody RM, Olsen CH, Harrison LH, Santosham M, Aronson NE. The Long-term Effect of Bacille Calmette-Guérin Vaccination on Tuberculin Skin Testing: A 55-Year Follow-Up Study. Chest. 2017;152(2):282-294. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.01.001

- So previous BCG vaccine should NOT influence decisions regarding interpretation of TST results (remember most individuals who receive BCG vaccine come from countries where incidence of TB is high)

- Intravesical administration of BCG for bladder cancer has been reported to convert TST in >=50% of patients, but again — should NOT result in positive IGRA

- IGRAs are not affected by BCG vaccination status so are useful for evaluation of LTBI in BCG-vaccinated individuals

- Quantiferon detects TB proteins ESAT-6, CFP-10, and TB7.7, which are not present in BCG [basis for specificity in BCG-vaccinated people]

- TB PCR detects sequence in katG which is present in M. bovis BCG

Complications of the BCG vaccine

- Localized skin reactions can follow BCG vaccination and are common (blue/red papule with pain, swelling; 2-3 wks after vaccination)

- More serious adverse effects can occur less often, and it is important to classify the type of disease.

- BCG lymphadenitis or abscess (1-2%), often accompanied by draining sinus tracts or fistula

- BCG osteomyelitis is another rare complication, which we discussed on the episode

- Can lead to bone deformity, fistulas, impaired growth of limbs

- Often presents 1-2 years after BCG vaccine

- Does NOT have to be related to the site of injection (most commonly in lower limbs) — it is thought to spread secondary to bacillemia rather that direct spread in many cases

- Key feature of the illness script is impressive radiographic findings with insidious clinical symptoms

- Some links in next section

- Disseminated BCG disease can occur in immunosuppressed individuals (intravesical BCG for bladder cancer) or young children with immunodeficiency (those with SCID, HIV)

Management of BCG osteomyelitis

- There are no RCTs for management. The best evidence we have is a systematic review of 331 cases published in 2015

- Generally medical therapy is recommended, although surgery might be considered in certain cases

- BCG M.bovis is resistant to pyrazinamide, so can treat with 3-drug regimen of rifampin, isoniazid, ethambutol

- Huang CY, Chiu NC, Chi H, Huang FY, Chang PH. Clinical Manifestations, Management, and Outcomes of Osteitis/Osteomyelitis Caused by Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guérin in Children: Comparison by Site(s) of Affected Bones. J Pediatr. 2019;207:97-102. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.11.042

- Miseviciene V, Liakaite G, Suciliene E, Ivaskeviciene I. Bacille Calmette-Guérin Vaccine-induced Osteomyelitis in Immunocompetent Children: A 10-year Case Series in Lithuania. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40(2):e77-e81. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000002981

- Lin WL, Chiu NC, Lee PH, et al. Management of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin osteomyelitis/osteitis in immunocompetent children-A systematic review. Vaccine. 2015;33(36):4391-4397. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.07.039

Is BCG osteomyelitis worrisome for an underlying immunodeficiency?

To date, genetic causes have not been identified for NTM lymphadenitis, pulmonary MAC, BCG osteomyelitis.

That being said, disseminated BCG disease (BCGosis) is concerning for immunodeficiency, in particular:

- Infants with SCID (severe combined immunodeficiency)

- Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease (MSMD)

- A heterogenous group of rare inherited defects that confer increased risk for mycobacterial infection, generally defects involved in communication between macrophages adn Th1 cells (IL-12 > IFNgamma pathways; kinases such as Tyk2 or transcription factors like STAT1)

- These patients have also been shown to have increased risk to other infections, such as Salmonella and mucocutaneous candidiasis

- Bustamante J. Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease: recent discoveries. Hum Genet. 2020;139(6-7):993-1000. doi:10.1007/s00439-020-02120-y

- van de Vosse E, van Dissel JT, Ottenhoff TH. Genetic deficiencies of innate immune signalling in human infectious disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(11):688-698. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70255-5

Of note, we also discussed that there are acquired defects in adult patients that impair IFNg signaling and can be associated with severe disseminated mycobacterial (NTM) infections and other opportunistic infections (such as neutralizing anti-IFNg autoantibodies). You can start some reading on that here:

- Aoki A, Sakagami T, Yoshizawa K, et al. Clinical Significance of Interferon-γ Neutralizing Autoantibodies Against Disseminated Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(8):1239-1245. doi:10.1093/cid/cix996

- Browne SK, Burbelo PD, Chetchotisakd P, et al. Adult-onset immunodeficiency in Thailand and Taiwan. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(8):725-734. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1111160

- Wongkulab P, Wipasa J, Chaiwarith R, Supparatpinyo K. Autoantibody to interferon-gamma associated with adult-onset immunodeficiency in non-HIV individuals in Northern Thailand. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e76371. Published 2013 Sep 27. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076371

Who is an immigrant or refugee? How should we think about medical screening in these children?

Often children who are born outside of the US are vulnerable to increased morbidity in our system due to lack of awareness of their migration journeys and indications for screening and treatment. Depending on legal characterization of the patient (refugee vs immigrant vs international adoptee), they will have varying encounters with healthcare prior to your encounter with them.

Let’s start with definitions, which are legal identifications:

- Refugee: any person who is unwilling or unable to return to their country of nationality due to persecution or fear of persecution. They have certain international legal protections and are resettled via asylum processing

- Many refugees are displaced out of country of nationality into refugee camps, which often have high density overcrowding, and therefore are prone to both environmental and public health hazards

- Once granted refugee status into a new country, the refugee is assigned to a resettlement city. Often after a certain period of time, refugee families undergo secondary migration to other locations to be close to known relatives and connections. This can lead to difficulty obtaining records (unknown vaccination status or medical history/treatments) and families might not be plugged into resources (delays in treatment, lack of access to adequate care)

- Immigrants are a population who move away from their country of nationality with intentions to become citizens in the new country of resettlement

Importance of screening

- As mentioned above, refugees are often displaced into overcrowded communities with poor sanitation and hygiene accessibility.

- Refugees typically undergo predeparture and domestic health screening and treatment after being chosen to relocate to the US

- Health services are provided and coordinated with the International Office of Migration

- It’s important to note that immigrant/migrant children do not undergo routine pre-departure or domestic health screening, and they may have variable predeparture environments. So these children may encounter the health system in more variable time frames and degrees

Describe pre-departure screening and presumptive treatment for refugee children

- M.tuberculosis specific screening:

- <2 years old: not indicated unless clinical or exposure history

- 2-15 years old: IGRA (CXR if positive or signs/symptoms; treatment if indicated)

- >15 years old: CXR (if suggestive, 3 sputum AFB smear/culture; treatment if indicated)

- HIV screening not required

- Presumptive treatment of selective parasites:

- Malaria: treatment if from endemic country

- **children <5kg should not receive presumptive treatment but can offer if infection detected

- Soil-transmitted helminths: albendazole x 1

- **children <1 year old should not receive presumptive treatment

- Strongyloidiasis: ivermectin

- only in Loa Loa nonendemic countries

- **children <15kg should not receive presumptive treatment

- Schistosomiasis: praziquantel

- **children <4 year old should not receive presumptive treatment

- Malaria: treatment if from endemic country

- Age-dependent vaccines, per CDC schedule

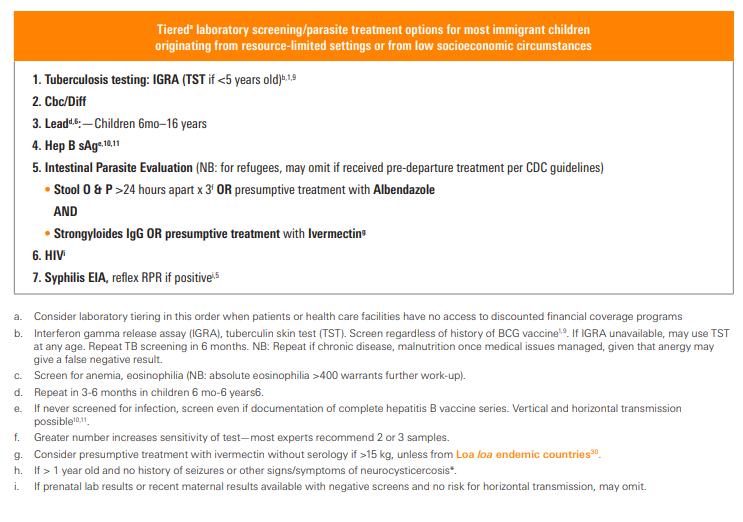

Describe arrival or domestic screening for both refugees and immigrant children from low and middle income countries

- CBC with differential

- Absolute eosinophil count and eosinophilia can pick up visceral larva migrans or parasitic disease

- Might have a clue for hemoglobinopathies, anemia (nutritional deficiencies vs intestinal parasites)

- Urinalysis

- Hematuria/RBCs can be clue to schistosomiasis (consider serology if from endemic country)

- Latent TB: IGRA if 2 years or older, TST if under 2 years old

- Lead

- TSH

- Hepatitis B serology

- Intestinal parasites (Ascaris, hookworm, whipworm, Strongyloides, Giardia)

- Stool O&P x 3

- Consider Giardia lamblia / Cryptosporidium stool testing

- Strongyloides IgG

- HIV

- RPR

- Hep C if clinically indicated

Check out these resources:

- Peds in Review article on caring for refugee children: Seery T, Boswell H, Lara A. Caring for Refugee Children. Pediatr Rev. 2015;36(8):323-340. doi:10.1542/pir.36-8-323

- AAP Immigrant Child Health Toolkit

- CDC Refugee Health Profiles: information for clinicians, public health providers, and resettlement agencies to help with medical screening and appropriate services for specific refugee groups

- CDC Overseas Refugee Health Guidance: check out for more information here including vaccination programs

Other miscellaneous mentions and notes:

- Like textbook references?

- Long, Principles and Practice of Pediatric ID, 5th Ed.:

- Chapter 4: Infectious Diseases in Refugee and Internationally Adopted Children

- Chapter 134: Mycobacterium tuberculosis >> BCG section

- Comprehensive Review of Infectious Diseases

- AAP Red Book

- Long, Principles and Practice of Pediatric ID, 5th Ed.:

Episode Art & Infographics

Goals

Listeners will be able to provide evaluation and management recommendations for suspected extrapulmonary mycobacterial disease.

Listeners will be able to apply guideline and evidence-based recommendations for screening of children coming to the United States as immigrants and refugees

Learning Objectives

After listening to this episode, listeners will be able to:

- Summarize the recommendations for new-arrival screening for immigrant and refugee children

- Recommend an appropriate microbiological evaluation for a granulomatous lesion

- Describe the global epidemiology of TB in children and adolescents

- Recommend an appropriate treatment regimen for BCG associated disease

Disclosures

Dr. Thielen has received research support from Merck in the form of an investigator-initiated research support grant (“The role of the microbiome in the outcome of human respiratory viral infections”) and an honorarium from Horizon for serving on Medical Affairs Virtual Advisory Board: Perspectives on Diagnosis and Management of Carriers of X-Linked CGD. Neither of these is discussed in this podcast episode.

Febrile podcast and hosts report no relevant financial disclosures

Citation

Thielen, B., Lehman, A., Goren, L., Dong, S. “#19: Finding a knee-dle in a haystack”. Febrile: A Cultured Podcast. https://player.captivate.fm/episode/4231bef5-c9ec-4a71-96e0-ddf6ac549ef5