Table of Contents

Credits

Host(s): Navina Birk, Sara Dong

Guest: George Alangaden

Writing: Navina Birk, George Alangaden, Sara Dong

Producing/Editing/Cover Art/Infographics: Sara Dong

Our Guests

Guest Co-Host

Navina Birk, MD

Raised in Michigan, Dr. Navina Birk attended medical school at Wayne State University and completed residency at Rush University in Chicago. She is now back in Michigan completing Infectious Diseases fellowship at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, Michigan. She is interested in both transplant and general ID

Guest Discussant

George Alangaden, MD

Dr. George Alangaden is a Clinical Professor of Medicine at Wayne State University and the Director of Transplant Infectious Diseases at Henry Ford Health in Detroit, Michigan. He completed his MBBS and MD at Goa Medical College – University of Bombay as well as MRCP at Royal College of Physicians, UK. He completed medical residency and ID fellowship at Wayne State University. His research interests include infections in cancer and transplant patients and hospital epidemiology

Culture

Navina mentioned her puppy, and George shared his love of magic!

Consult Notes

Case Summary

42 yo female s/p heart transplant with recurrent Gram-negative bacteremias who was found to have donor-derived strongyloidiasis

Key Points

Navina and George touched on LVAD specific infections at the start of the case.

Check out this prior Febrile episode #30 for more background on VAD infections!

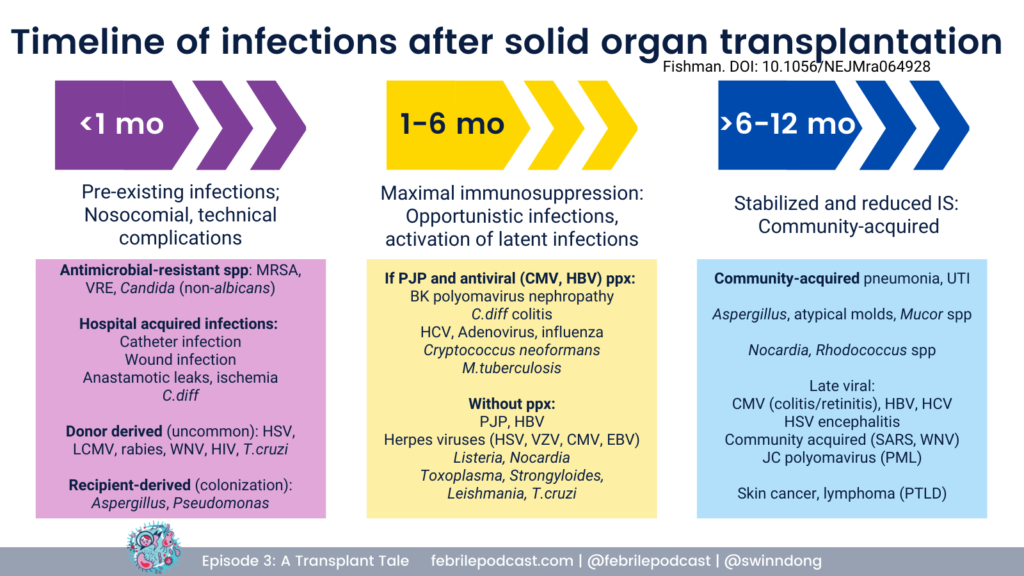

George reviewed that infectious complications post-transplant follow a specific temporal pattern.

For a refresher you can check out the graphic below (and listen to Febrile episode #3)

Introduction to donor-derived infections: infections present in the donor that are transmitted to one or more recipient(s)

- One of the inherent risks of solid organ transplantation is the transmission of disease from the donor to the recipient

- These can be expected or unexpected:

- With an expected transmission, since the donor is known to be infected with the pathogen, microbiologic monitoring, with pre‐emptive therapy and/or universal prophylaxis, is utilized to minimize the impact of the disease transmissions >> example is CMV

- With unexpected transmission, infection may occur despite routine extensive clinical and laboratory screening of the donor. Such transmissions occur when either clinical disease in the donor was not recognized at the time of donor death, or screening was not performed for the pathogen of interest

- The Disease Transmission Advisory Committee of the OPTN (Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network) evaluated all reported cases of possible disease transmitted from solid organ donors over 10 years from 2008-2017

- In the US, probably or proven donor-derived disease transmission is rare and occurs in <0.2% of all transplant done

We are concerned for a donor-derived infection - what are the initial steps?

- It is critical to immediately alert the local organ procurement organization (OPO) and UNOS (United Network for Organ Sharing) if a donor transmitted infection is suspected

- The OPO can help provide more information about the donor, and they will notify other transplant centers to check on the status of other recipients of organs from the same donor

- It should be emphasized that reporting should not await confirmation of transmission- it is prudent to contact the involved laboratory to save any residual fluids/tissues to facilitate the investigation and ensure that they will be held and not disposed

- Review donor origin and cultures

- Keep in mind common processes that can mirror donor-derived diseases, such as wound or surgical sites infections, graft rejection, anastomotic leaks, vascular compromise, drug toxicity, pneumonia, or Clostridium difficile colitis, must be evaluated

- In general, when an infection is identified in the donor, the recipient is treated with appropriate antimicrobial therapy directed against the pathogen for a duration that one would use if the recipient themselves had the infection

- Further, it is currently recommended that all recipients of organs from donors with identified risk factors for HIV, HBV, and HCV be tested post-transplant. Such testing must include methods that directly detect the actual virus (ie, HIV and HCV NAT and HBsAg) rather than rely solely on serology, as many patients will fail to develop detectable antibodies (ie, HCV antibody) post-transplant

- Current guidelines recommend testing for HIV, HBV, and HCV at 1-3 months and HBV at 12 months. Emerging data suggest that patients will rapidly develop detectable viral loads for HCV and patients with ongoing HCV replication may progress to fibrosis and/or cirrhosis quickly post-transplant. As a result, it is highly advisable to perform the initial screening PCR tests as close to the 1-month mark as possible.

- Check out the American Society of Transplantation Guidelines: Wolfe CR, Ison MG; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Donor-derived infections: Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant. 2019;33(9):e13547. doi:10.1111/ctr.13547

- Some additional resources:

- Chong PP, Razonable RR. Diagnostic and management strategies for donor-derived infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27(2):253-270. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2013.02.001

- Fishman JA, Greenwald MA, Grossi PA. Transmission of infection with human allografts: essential considerations in donor screening. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(5):720-727. doi:10.1093/cid/cis519

What screening is done in organ donors?

- Questions/Information related to the donor assessment includes:

- How did the donor die?

- How long was the donor hospitalized?

- Review cause of death and terminal illnesses

- Review chart for all positive culture, serology, nucleic acid testing/PCR/viral results

- Social history from close contact of donor

- Travel history

- High-risk behaviors

- Assess body for infection, abscesses, ulcers, genital or anal trauma, unexplained rash, lymphadenopathy, recent drug use

- Surgeons should assess the explanted organs and vessels – making sure there is no obvious pus, infection, lymphadenopathy

- Echocardiography and CT scanning may be useful

- Screening:

- HCV with both serology and NAT

- HIV NAT

- HBV NAT

- Other transmissible infections to consider depending on geography, time constraints: Tuberculosis, Chagas disease, West Nile virus, Trypanosoma cruzi, Zika virus, Strongyloides

- Living donors- donors with exposure to geographically defined endemic diseases such as Chagas, tuberculosis, HTLV, HHV8, strongyloides, and toxoplasmosis should be tested for this infection with serology; West Nile virus and other arboviruses that warrant screening should utilize NAT

- 28 days for NAT for HIV, HBV, HCV

- 14 days per AST guidelines

- 7 days for increased risk donors

Approach to donors with DOCUMENTED infections at time of procurement

- Active bacterial or fungal infection should be treated in resolved prior to transplant in an ideal situation

- Organs known to be infected with pathogens likely to be transmitted to the recipient should NOT be transplanted unless they can be safely treated

- Bacteremic Donors

- 5% of organ donors have bacteremia at time of organ procurement

- Generally, bacteria not susceptible to typically utilized perioperative antibiotics

- If transmitted, can see graft loss, morbidity, mortality but discarding these organs limit our already limited donor pool

- Gram negative bacilli pose greater risk than gram positive bacteria. Associated with poorer outcomes

- Greatest concern is MDR bacteria, especially carbapenem resistant bacteria

- When can we use a bacteremic donor?

- Donor receives targeted antimicrobial treatment for 24-48 hours

- Some degree is clinical response is witnessed (improved WBC count, improved hemodynamics, defervescence)

- Recipient can be treated with 7-14 day course of antibiotics targeted to the organism isolated from the donor

- Infectious Encephalitis Donors- if unknown cause- avoid!

- Bacterial meningitis is okay

- Donors with proven Naegleria fowlerii meningoencephalitis. Naegleria infection is generally limited to the CNS; even when there is molecular evidence of the parasite outside the CNS, transmission has not been documented. If the donor has proven N fowlerii meningoencephalitis, the organs can be utilized with a low risk of transmission, as long as the recipients are informed of the risk and monitored closely

When evaluating a patient for donor derived infection, what are the key points that every ID fellow should know?

- When DDI transmission occurred, ~70% of recipients manifest symptoms within 30 days

- Bacterial infections manifested earliest followed by viral

- Endemic fungal infection, mycobacterial, and parasite infections generally manifested after 30 days

- One of George’s take-home points: The diagnosis of DDI is almost always based on clinical suspicion! So when would you suspect DDI? When you encounter:

- A clinical illness outside of the expected timeline of infections after transplant

- A pathogen that is out of place given the epidemiological setting/history

- It is really important to contact the OPO if suspected DDI >> detection of clusters of the same infection in recipients from same donor clinically confirms the diagnosis

- Then laboratory confirmation can be done using archived donor and recipient sera and other tissues

Shifting gears - Navina provided some background on Strongyloides!

- A roundworm (nematode) that causes the disease known as strongyloidiasis

- Affects >600 million people worldwide, often causing chronic infection that can become life-threatening in certain cases

- Epidemiology:

- Most prevalent in tropical and subtropical climates, especially in areas with suboptimal sanitary conditions

- >70% prevalence in Peru, Kenya, Namibia, Papua New Guinea

- In the United States, most cases are considered imported but local transmission has been reported in rural areas. Most US infections have occurred in southeastern states and Appalachian regions

- Increased risk of infection- HIV, HTLV, hypogammaglobulinemia, alcoholism malnutrition

- Most prevalent in tropical and subtropical climates, especially in areas with suboptimal sanitary conditions

- Resources/references:

- Czeresnia JM, Weiss LM. Strongyloides stercoralis. Lung. 2022;200(2):141-148. doi:10.1007/s00408-022-00528-z

- Buonfrate D, Bisanzio D, Giorli G, et al. The Global Prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis Infection. Pathogens. 2020;9(6):468. Published 2020 Jun 13. doi:10.3390/pathogens9060468

- Lindrose AR, Mitra I, Fraser J, Mitre E, Hickey PW. Helminth infections in the US military: from strongyloidiasis to schistosomiasis. J Travel Med. 2021;28(6):taab004. doi:10.1093/jtm/taab004

- Inagaki K, Bradbury RS, Hobbs CV. Hospitalizations Associated With Strongyloidiasis in the United States, 2003-2018. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75(9):1548-1555. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac220

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notes from the field: Strongyloidiasis in a rural setting–Southeastern Kentucky, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(42):843.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notes from the field: strongyloides infection among patients at a long-term care facility–Florida, 2010-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(42):844.

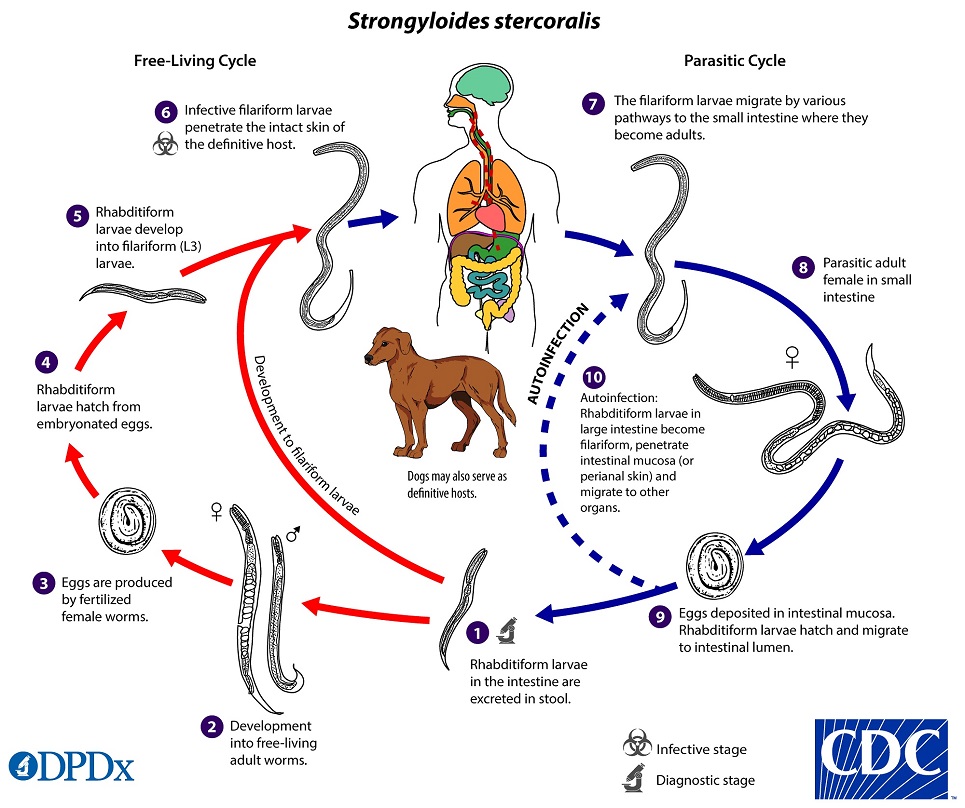

What is the life cycle of Strongyloides?

- Infects humans through cutaneous route

- Infective filariform larvae of Strongyloides infects humans by penetrating the skin

- Often penetrate skin of people who are walking barefoot, “ground itch”

- After penetration, filariform larvae migrate to the lungs (via bloodstream and lymphatics)

- Larvae are coughed up, swallowed, and progress to GI tract

- In the small intestine, the larvae mature into adult females

- They produce eggs through asexual reproduction that hatch into rhabditiform larvae, and are excreted into stool

- These rhabditiform larvae (non-infectious) give rise to infectious filariform larvae within intestine or soil

- If filariform larvae are generated in the host, they invade the intestinal mucosa and restart the cycle >> this turns into a chronic infectious cycle

- Filariform larvae can be ingested from contaminated food, water, or anal-oral contact to cause primary infection

- Autoinfection can occur when filariform larvae penetrate intestinal mucosa and migrate to other organs

What is the clinical spectrum of disease of strongyloidiasis?

- Acute

- Host- Person with recent exposure to endemic area

- Presentation

- Larva currens “running larvae”- include picture

- Loeffler-like syndrome

- Heartburn

- Anorexia

- Abdominal pain

- Constipation

- Diarrhea

- Chronic

- Host- Person with remote exposure to endemic area

- Presentation

- Often asymptomatic

- Intermittent nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain

- Pruritis ani

- Urticaria

- Recurrent asthma

- Eosinophilia

- Chronic

- Host- Person with remote exposure to endemic area AND

- Immunosuppression

- Bone marrow transplant or Solid organ transplant

- HTLV-1 Infection

- Hypogammahlobulinemia

- Hematologic malignancies

- Presentation- Multi organ manifestations, discussed below

- Host- Person with remote exposure to endemic area AND

Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome

- Typically occurs when patients with chronic infection become immunosuppressed (often triggered by steroids), which leads to a dramatic increase in the rate of autoinfection and parasitic burden

- The dissemination of larvae through tissues causes direct damage, and disruption of the intestinal membrane predisposes to bacteremia caused by intestinal flora

- It is during the autoinfection process that gut pathogens (usually GNB and Enterococci) hitch a ride with the larvae into the blood, causing bloodstream infections

- Classic presentation with recurrent, unexplained enterobacterial, polymicrobial bloodstream infections; however presentation is highly variable

- Lung is an important target

- Pneumonia and cough are seen from the migrating filiform larvae in the pulmonary parenchyma

- Chest Radiographs show bilateral interstitial and parenchymal infiltrates, focal infiltrates also reported

- Significant gastrointestinal symptoms: abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, ileus

- Other manifestations include meningitis with enteric flora and larval invasions of other organs (pancreas, liver, kidneys)

- Mortality of untreated strongyloides hyperinfection is 85-100%

- Most common trigger is steroids- multiple cases of SHS reported following use of steroids for COVID-19

- Patients with COPD or asthma from endemic regions should be screened prior to starting steroids, can trigger hyper infection syndrome

- In transplant:

- Donors may have chronic infection with Strongyloides, or infection can be transmitted during transplantation, such as in the episode’s case

- Antirejection regimens cause impaired host immunity by depressing the innate immune eosinophilic response and downregulating the adaptive Th2 immune response >> this leads to accelerated autoinfection and devastatin increase in migrating larvae and widespread dissemination

- More info related to Strongy in transplant:

- AST Guideline

- Abanyie FA, Gray EB, Delli Carpini KW, et al. Donor-derived Strongyloides stercoralis infection in solid organ transplant recipients in the United States, 2009-2013. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(5):1369-1375. doi:10.1111/ajt.13137

- Abad CLR, Bhaimia E, Schuetz AN, Razonable RR. A comprehensive review of Strongyloides stercoralis infection after solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2022;36(11):e14795. doi:10.1111/ctr.14795

Diagnosis of strongyloidiasis

- Gold Standard for Parasitological Testing: Direct visualization of larvae

- Sensitivity of single specimen stool microscopy is as low as 21%

- Increases to 100% when 7 samples are sent

- During hyperinfection, the large number of worms makes detection easier

- Can also use PCR, but estimates of sensitivity and specificity are variable

- Serologic testing- can be used in chronic stongyloides in low parasitic burden

- For patients with in low prevalence setting, negative predictive value approaches 100%

- Do not rely on for acute infections and if high clinical suspicion

Management of strongyloidiasis

- Drug of Choice: Ivermectin

- If uncomplicated or screening with positive serology, oral ivermectin 200 μg/kg/day for two consecutive days

- Can consider repeating the course after 2 weeks

- In randomized clinical trials, single dose ivermectin has shown similar efficacy to multiple dose regimens

- If hyperinfection:

- Ivermectin daily at 200 μg/kg/day for at least two weeks and until clinical improvement

- Ideally, treatment should be extended until no more larvae are found in stool and/or respiratory specimens

- Reduction in immunosuppression as able, especially steroids

- If oral administration is not possible or intestinal absorption impaired:

- Rectal ivermectin (not FDA approved)

- Parenteral (subcutaneous) ivermectin – last resort

- Reports of successful treatment with addition of albendazole to ivermectin

- Ivermectin daily at 200 μg/kg/day for at least two weeks and until clinical improvement

- Patients are considered infectious, should be on standard contact precautions

How to screen donors and recipients at risk for strongyloidiasis?

- Current guidance by the American Society of Transplantation is to perform targeted risk-based screening of persons (donors and recipients) who were born or lived in endemic regions of the world where sanitation conditions are substandard, persons with unexplained eosinophilia, persons born in US in Appalachia or in southeastern US

- Serologic testing is the preferred method for screening

- If living donor or recipient is seropositive, then treatment with ivermectin should be given

- If deceased donor is seropositive, then prophylaxis with ivermectin should be given to recipient

- Resources:

Infographics

Goal

Listeners will be able to recognize features suggestive of donor-derived infection in solid organ transplant recipients

Learning Objectives

After listening to this episode, listeners will be able to:

- Define donor-derived infection (DDI) in transplantation and identify the importance of alerting organ procurement organizations if DDI is suspected

- Discuss the life cycle of Strongyloides

- Compare the treatment of strongyloidiasis in uncomplicated or screening diagnoses vs hyperinfection syndrome

Disclosures

Our guests (Navina Birk, George Alangaden) as well as Febrile podcast and hosts report no relevant financial disclosures

Citation

Alangaden, G., Birk, N., Dong, S. “#68: An Unexpected [Donor-Derived] Pathogen”. Febrile: A Cultured Podcast. https://player.captivate.fm/episode/819b7857-d8a9-4afe-ad75-ec0198d53b15