Table of Contents

Credits

Hosts: Amedine Duret, Sara Dong

Guest: Liz Whittaker

Writing: Justin Penner

Producing/Editing/Cover Art: Sara Dong

Our Guests

Dr Amedine Duret

Dr Amedine Duret is a National Institute for Health and Care Research Academic Clinical Fellow in paediatric infectious diseases, working at Imperial College London. She completed her medical degree at the University of Cambridge before joining the department for paediatric infectious diseases at St Mary’s Hospital in London. She was part of the British Association for Paediatric Tuberculosis Expert Writing Group who published national guidance on the care of children with tuberculosis, and led on a national survey of practice on paediatric tuberculosis in the UK. Her academic research focuses on the role of rare genetic variants in life-threatening infections.

Dr Liz Whittaker

Dr Liz Whittaker is Senior Clinical Lecturer in paediatric infectious diseases and immunology. She divides her time between Imperial College London and the Department of Paediatric Infectious Diseases and Immunology, St. Marys Hospital, London where she is a Consultant. Dr. Whittaker is the Director of Research for West London Children’s Healthcare (WLCH), working closely with the Board of WLCH and Imperial College’s Centre of Paediatrics and Child Health (PAECH) to ensure research is embedded in every patient’s journey. Dr Whittaker is the Clinical Lead for Paediatric Infectious Diseases and the co-lead for HCID (high consequence infectious diseases) at St Marys, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust. She is the Convenor of the British Paediatric Allergy Infection and Immunity Group (BPAIIG; BPAIIG). She is on the steering committee of the British Association of Paediatric Tuberculosis (BAPT) and works closely with international colleagues in Europe and beyond to improve diagnosis and outcomes in children with TB, through the PTBNET group amongst others. Her main research interests are the ontogeny of infant immune responses to a variety of pathogens. Her PhD data suggest that children under a year of age have an immaturity of their non-specific T cells or innate immune responses in conjunction with increased numbers of regulatory T cells. She expanded on this theme while an NIHR funded ACL and now by creating generic and specific assays that will examine the maturation of immune responses in children of different ages, from premature infants of different gestation to older children with ‘mature’ immune systems. The aim of this research is to develop biomarkers of infection for diagnostic purposes in neonates and to understand differences in immature immune responses that may lead to protection for this vulnerable group, either through vaccinations or immunomodulatory interventions in pregnancy and/or the early neonatal period. Understanding these differences is essential for the development of new adjuvants which will increase the efficacy of neonatal vaccinations to such pathogens as CMV, Group B streptococcus & RSV. Her PhD students work on the impact of viral co-infection on tuberculosis (TB) susceptibility as well as factors that lead to increased susceptibility to TB disease and infection in adolescents. Liz is the paediatric specialty co-lead for the northwest London Clinical Research Network. In this role, she leads the development of local clinical research network activity in paediatrics, encouraging local clinicians to participate in NIHR clinical research network portfolio studies. She is PI of a number of commercial and non-commercial studies on the NIHR portfolio. Liz is the Convener of the British Paediatric Allergy, Immunity and Infection Group (BPAIIG) and co-lead of the British Association of Paediatric TB (BAPT). Liz completed her Wellcome Trust funded PhD project “Immune responses to mycobacteria; the role of age and disease severity” in 2014. The project was supervised by Professor Beate Kampmann at Imperial College and Professors Mark Nicol and Heather Zar at the University of Cape Town, where all of the children were recruited at Red Cross Memorial Children’s Hospital. She was fortunate to complete her lab work in the Institute of Infectious Disease and Molecular Medicine in Cape Town, working closely with both Clinical Infectious Diseases Research Initiative (CIDRI) and the South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative (SATVI). She completed her undergraduate training in medicine at Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland, including an HRB (Health Research Board) funded BSc in Biochemistry. This included a basic research project ‘The role of NFkappaB in 5-Lipoxygenase activation’ with Prof. Luke O’Neill for which she won the Bruno Orsi Medal for best research project. Following this she trained as a paediatrician in London and was successfully awarded an Academic Clinical Fellowship in Paediatric Infectious Diseases in 2006. The 9 month research period associated with this fellowship allowed her to develop her interest in paediatric infectious diseases and involved a couple of research projects (on TB Biomarkers and Interferon Gamma Release Assays) which resulted in a number of presentations and publications. During this time she was also involved in the setting up of a paediatric TB Europe Network to facilitate collaboration between Paediatricians caring for children with TB and improved care for children with TB in Europe. She completed the Gorgas Diploma Course in Clinical Tropical Medicine in Peru and was awarded a DTM&H in 2009. She is a member of IMPRINT and INVAR networks.

Culture

Amedine and Liz both shared how they’ve enjoyed open water swimming and experiencing the beautiful outdoors

Consult Notes

Consult Q

You are called by the NICU about an 18 day old baby born at 30+6 who developed feeding intolerance, respiratory distress, and temperature instability.

Key Points

Welcome to our second edition of “Curious Congenital Conundrums”!

This episode is part of a set of 4 (including 79, 80, 81, 82). If you missed the prior congenital series from the previous season, you can check out episodes 36, 37, 39, 41, 43 where we discussed the framework of SCORTCH (as opposed to TORCH) and 4 cases of CMV, syphilis, toxoplasma, and HSV in pregnancy and the congenital or neonatal setting.

Background/Epidemiology/Transmission

- Congenital TB is rare

- Can be acquired hematogenously via placenta and umbilical vein (producing primary lesions in the liver or lung usually) or via fetal aspiration (or ingestion) of infected amniotic fluid (producing primary lesions in lung or digestive tract typically

- It occurs most often in the setting of material TB endometritis or disseminated TB (after maternal bacillemia)

- Has also been reported following in vitro fertilization of women from countries with endemic disease in whom infertility likely was related to subclinical maternal genitourinary tract TB

- Neonatal TB develops following postnatal exposure to aerosolized respiratory secretions of a contagious person, typically the infant’s mother

- Some may use the term perinatal TB instead of congenital TB – as distinguishing it from early postnatal acquired TB is a matter of epidemiological importance (they do not differ much with regard to presentation, treatment, prognosis) and it is challenging to differentiate in real cases as well >> perinatal TB would refer to infection with MTB that occurs in utero, at birth, or during the early newborn period

- It’s difficult to determine the true incidence. There are over ~300-400 cases reported in the English literature

- Some resources/references:

- Shao Y, Hageman JR, Shulman ST. Congenital and Perinatal Tuberculosis. Neoreviews. 2021 Sep;22(9):e600-e605. doi: 10.1542/neo.22-9-e600. PMID: 34470761.

- Peng W, Yang J, Liu E. Analysis of 170 cases of congenital TB reported in the literature between 1946 and 2009. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011 Dec;46(12):1215-24. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21490. Epub 2011 May 27. PMID: 21626715.

- Ferreras-Antolín L, Caro-Aguilera P, Pérez-Ruíz E, Moreno-Pérez D, Pérez-Frías FJ. Perinatal Tuberculosis: Is It a Forgotten Disease?. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37(3):e81-e83. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000001830

- Whittaker E, Kampmann B. Perinatal tuberculosis: new challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in infants and the newborn. Early Hum Dev. 2008;84(12):795-799. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.09.005

- Mathad JS, Gupta A. Tuberculosis in pregnant and postpartum women: epidemiology, management, and research gaps. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(11):1532-1549. doi:10.1093/cid/cis732

Clinical manifestations

- Congenital TB can have variable presentations

- Congenital TB can mimic neonatal sepsis as none of the possible signs (such as fever, tachypnea, lethargy, organomegaly, or pulmonary infiltrates) can distinguish it from other systemic infections of the newborn

- As discussed in this episode (as well as other CCC episodes!), there is a very broad differential – so it’s important to gather information about the baby as well as the maternal status and background

- Based on available literature, the symptoms in newborn usually occur from the 2nd or 3rd week of life although onset may be delayed until several months of life – Symptoms can occur at birth though and earlier presentations are generally associated with more severe disease

- Mortality rates are high and likely complicated by delayed diagnosis

This case discussed an example case where a mother had tuberculosis disease

- Management of a newborn is based on categorization of maternal infection. Some circumstances and general recommendations (from the 2021-2024 AAP Red Book) are noted below:

- Mother has positive TST or IGRA result with normal CXR

- If mother is asymptomatic, no separation is required

- Mother is usually a candidate for treatment after initial postpartum period

- Newborn infant needs no special evaluation or therapy

- Ensure that there is not an unrecognized case of contagious TB within household

- Mother has clinical signs/symptoms or abnormal findings on CXR consistent with TB disease

- If mother has TB disease, infant should be evaluated for congenital TB

- Mother and infant should be separated until mother has been evaluated → if TB disease is suspected, ideally would separate until mother and infant are receiving appropriate anti-TB therapy, mother wears mask, and mother understands/adheres to infection control measures

- Women with TB who have been treated appropriately for 2 or more weeks and who are no longer contagious (smear-negative sputum) may breastfeed; Women with TB disease suspected of being contagious should refrain from breastfeeding and other close contact due to risk of potential spread → ok to use expressed human milk unless mother has signs of tuberculous mastitis which is rare

- If congenital TB is excluded, isoniazid is administered until infant is 3-4 months of age, when a TST should be performed

- If TST negative and mother has good adherence/response to treatment/no longer contagious, isoniazid should be discontinued for baby

- If TST is positive, infant should be reassessed for TB disease. If TB disease is excluded, isoniazid should be continued for total of 9 months (or a 4 month course of rifampin can be given)

- Mother has positive TST or IGRA result with abnormal CXR but no evidence of TB disease

- Infant is at low risk of TB infection and need not be separated from mother

- Still ensure household members are evaluated

- Mother has positive TST or IGRA result with normal CXR

Diagnosis

- There were diagnostic criteria for distinguishing congenital TB from postnatally acquired TB proposed by Beitzke in 1935:

- These required the infant have proven tuberculous lesions and one of the following: lesions in first few days of life, a primary hepatic complex, or the exclusion of postnatal transmission by the separation of infant at birth from mother and other sources of infection

- Beitzke H. Uber die angeborene tuberkulose Infektion. Ergeb Ges Tuberk Forsch 1935;7:1-30

- Since these Beitzke criteria were quite rigid (requiring TB to be bacteriologically proven and disease established in the first few days of life), Cantwell et al proposed some modifications:

- Neonates should have proven tubercular lesions and at least one of the following: lesions in the first week of life, primary hepatic complex or caseating hepatic granulomas, tuberculous infection of the placenta or the maternal genital tract, or exclusion of the possibility of postnatal transmission by a thorough investigation of contacts and by adherence to existing recommendations for treating infants exposed to TB

- Cantwell MF, Shehab ZM, Costello AM, et al. Brief report: congenital tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(15):1051-1054. doi:10.1056/NEJM199404143301505

- If congenital TB is suspected, it is important to obtain samples in both the baby and mother.

- Evaluation for baby would likely include:

- TST: TST results are usually negative in newborn infants with congenital or perinatally acquired infection

- IGRA test: IGRA sensitivity in this context is not known but is likely low

- Chest radiography: variable radiographic changes may be seen ranging from miliary pattern to nodules to cavitation

- Routine labs (CBC/diff, complete metabolic panel)

- Lumbar puncture to rule out CNS disease

- Appropriate cultures

- Gastric aspirates are generally collected first thing in the morning x 3

- Skin lesion biopsies if appropriate, etc

- May also need to consider additional studies such as:

- Abdominal US for hepatosplenic lesions

- Head imaging

- Stool mycobacterial PCR

- As we’ve also discussed in prior CCC episodes, neonates with suspected TB should also have screening for other congenital infections

- Mothers should be evaluated for presence of pulmonary or extrapulmonary disease, including genitourinary tuberculosis

- TST/IGRA

- Sputum or BAL samples and other appropriate AFB culture sampling as indicated

- If possible and TB is suspected, placenta should be examined histologically for granulomas; AFB smear and culture

- HIV testing of the mother is essential as well

Treatment

- REGARDLESS of TST or IGRA results, treatment should be initiated promptly

- The treatment will be impacted by susceptibilities of maternal strain if known. Typical regimen includes two months of 4 drugs:

- Rifampin

- Isoniazid

- Pyrazinamide, and

- Either ethambutol or an aminoglycoside (streptomycin, kanamycin, amikacin) or capreomycin

- –

- Followed by several months of 2 drugs (typically isoniazid and rifampicin) depending on whether infant has pulmonary TB (6 months total treatment) or disseminated disease with CNS involvement (12 months total treatment)

- Given perinatal TB is uncommon, there are no trials to assist in determining the optimal type or duration of treatment, although these noted durations with maintenance treatment of 6-12 months (or extended with resistance) are usually observed

- As Liz mentioned, we also don’t have great PK data for these drugs in neonates, especially those that are preterm

- So therapeutic drug monitoring can be used (usually a pre and 1-hr-post level)

- It’s also important to determine whether the baby is tolerating feeds and oral meds, because we might need to provide the drugs intravenously (there are IV preparations of isoniazid and rifampicin – but will need additional agents which might include a fluoroquinolone, linezolid)

- Liz discussed the side effects of TB treatment

- Hepatotoxicity is the most common

- Those with liver lesions from their TB may also be at slightly higher risk

- Would also need to ensure there are not additional risk factors for transaminitis or adverse liver event in terms of hepatitis or HIV

- Certain medications such as moxifloxacin would increase risk of QT prolongation, so need to monitor EKGs

- Bone marrow suppression

- Here is the TB Drug Monograph website that Liz mentioned, which provides guidance on these antimycobacterial drugs

- Hepatotoxicity is the most common

- Corticosteroids are not routinely indicated, but these are generally recommended in cases of:

- CNS disease

- Miliary TB

- Pleural, pericardial, or endobronchial involvement (causing airway obstruction)

- There are variable recommendations on use of steroids in various settings, so make sure to discuss with your local TB expert

- A suggested dosing would be use of prednisone 1-2 mg/kg/day PO x 4-6 weeks with gradual weaning

- What if there are concerns or confirmation of MDR TB in the mother?

- These are complex and require working with a good multidisciplinary team

- MDR TB is difficult to treat because the second line antibiotics available are not as good at sterilizing and killing mycobacteria and often the regimens have more toxicity→ plus we still are limited on data/PK of these drugs in preterm infants

- Liz mentioned the British Thoracic Society expert clinical expert advice service, where cases like this can be discussed including pharmacy, medicine, and nursing: https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/lung-disease-registries/bts-mdr-tb-clinical-advice-service/

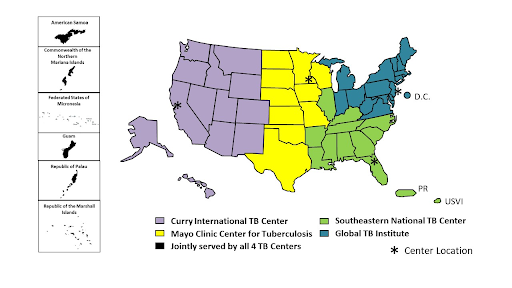

- In the US, expert guidance can be obtained through the CDC TB Centers of Excellence

- There is guidance from the WHO and other bodies on how to best construct a regimen, including usually drugs such as bedaquiline, linezolid, quinolones, clofazimine, delamanid

- Liz also mentioned the challenges with breastfeeding and some of the MDR-TB drugs, which are secreted in breast milk → so would need to think carefully about which drugs to use and what to recommend for mom related to breastfeeding

- Also remember that durations of treatment for MDR-TB are often 18-24 months of treatment, where the toxicity tends to contribute even if you don’t have issues in the beginning

- It’s also worth noting that the antibiotics often don’t have a pediatric friendly formulation

- This would also impact the discussion of screening and prophylaxis for the other babies on the unit (again would be a MDT approach, may have limited options)

Infection control and prevention measures

- Typically a case like this episode would represent paucibacilliary disease, thus transmission to others from the baby is quite low → but other factors are at play (such as duration of exposure, aerosol generating procedures, factors that increase susceptibility, etc).

- Liz discussed aspects of infection control in the episode, which we won’t detail here. A key learning point though is to ensure that household members have screening/evaluation

- Liz also discussed providing chemoprophylaxis to other babies on the unit. One key point is that she discussed repeat testing at the end, but important to note the challenge of using TST/IGRA (as they are immune tests that rely on baby’s ability to mount a cell mediated immune response and they are not very reliable in young children)

- Would not base decision making for providing prophylaxis to babies on results of these tests but can think about results as information and knowing how far to search for evidence of disease in the infant

- Liz also discussed that the decision of whether to provide BCG to baby at the end of prophylaxis course would be a case by case discussion with MDT, family, and depending on local policy/epidemiology

Infographics

Goal

Listeners will be able to understand the clinical presentation and evaluation of perinatal tuberculosis infection

Learning Objectives

After listening to this episode, listeners will be able to:

- List some of the clinical features of congenital tuberculosis

- Describe the recommended treatment for perinatal TB and anticipated adverse effects

- Discuss the impact of maternal MDR-TB on decision making for treatment of neonatal TB

Disclosures

Our guests (Amedine Duret and Liz Whittaker) as well as Febrile podcast and hosts report no relevant financial disclosures

Citation

Duret, A., Whittaker, L., Dong, S. “#79: Curious Congenital Conundrums – Mycobacterial Malady”. Febrile: A Cultured Podcast. https://player.captivate.fm/episode/131457a8-b9f0-4d36-bf93-c44e077921cd