Credits

Host: Sara Dong

Guest: Gerome Escota

Writing/Producing/Editing/Cover Art/Infographics: Sara Dong

Dr. Escota is the co-Program Director of the Infectious Diseases Fellowship and the Medicine Clerkship Director at Washington University in St. Louis. He is a member of the executive committee of the IDSA Medical Education Community of Practice and chairs its Teaching and Learning Resources Workgroup. Gerome is originally from the Philippines and has a long list of teachers that have inspired him to be an ID educator. More recently, he has expanded this role on social media by creating @WuidQ, the first Twitter resource that provides a platform for ID teaching and learning via board-style questions and case discussions. He is a dutiful son, a caring brother, a trusted friend, an approachable teacher, a lifelong learner, and always a wide-eyed camper.

Also check out Comprehensive Review of Infectious Diseases, 1st edition, a must-have book for ID fellows!!

Culture

Gerome’s recommendation was enjoying anything related to food! Check out some recommended recipes from Gerome and Sara below:

Consult Notes

Consult Q

Patient with brain and lung lesions who presented with fatigue. Please assist with work-up

One-liner

70 yo F with history of a cavitary pulmonary nodule and parietal brain lesions who presented with fatigue and anorexia. She was ultimately found to have disseminated Aspergillus fumigatus infection with endocarditis, bilateral endophthalmitis, pulmonary, and CNS disease.

Key Points

Tips on how to approach a complicated patient

- “It is not uncommon for one to get overwhelmed when hearing about a complicated case and when you start actually digging into the file and assembling relevant information about consult.”

- Summarize the case

- Look at your patient and host factors — what are the important risk factors that might predispose to certain infections? These could include age, immunosuppression, steroid use, prior splenectomy, etc

- Look at the signs, symptoms – try to come up with a grouping of symptoms into a recognizable clinical syndrome

- Here you can weave in the tempo of illness – is it chronic? Gradual onset or sudden evolution?

- Take into account labs and imaging to help align with possible syndromes

- Combining your summary of the patient and the summary of the syndrome = your problem representation

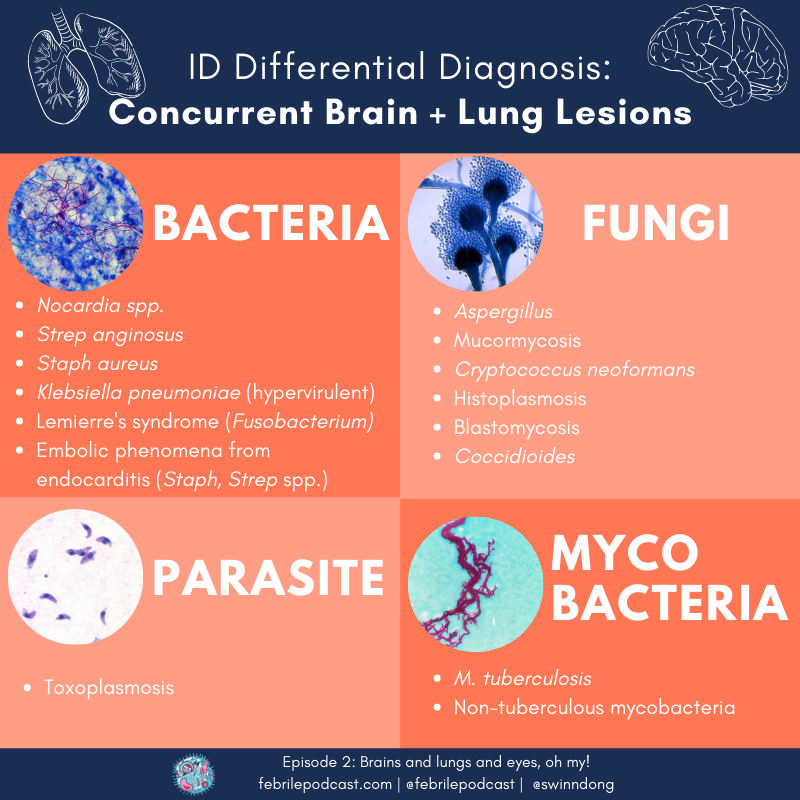

A common clinical syndrome for ID consults is the co-occurence of brain and lung lesions. Keep these infections on your differential diagnosis!

- Nocardia spp.

- Fungal infections:

- Endemic fungi, depending on epidemiology(Dr. Escota abbreviated as ‘HBC’ = Histoplasma, Blastomycoses, Coccidiomycoses)

- Yeast (Cryptococcus)

- Mold (Aspergillus, Mucor)

- Embolic disease:

- Cardiac is prototypical: look for infective endocarditis (Staph, Strep – but also other less common organisms that might cause endocarditis)

- Non-cardiac embolizing disease can include Lemierre’s disease (often Fusobacterium), infectious aortitis, infected cardiac thrombus

- Organisms predisposed to dissemination: hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Mycobacterial disease: M.tuberculosis, non-tuberculous mycobacteria

- Check out these organisms on one of the episode infographics!

In this episode, we discussed the ID approach when you have a patient with ongoing disease while on therapy. Here are some considerations in that setting:

- Source control is key! Must ensure that failure or progression while on therapy is not related to lack of source control.

- Wrong bug?

- Do you have the right causative organism identified?

- Is there co-infection?

- Is there an additional non-infectious process going on?

- Wrong drug?

- Do you have the right drug at the right dose?

- In this case, we considered whether voriconazole could be subtherapeutic. Therapeutic drug monitoring is used, but voriconazole has non-linear kinetics — meaning increases or decreases in the dose do not directly predict what the drug level will do

- Is the patient taking the medication? Is there an absorption issue?

- Are there drug interactions or toxicities?

- Does the drug penetrate the area of concern? This is typically going to be more of a question with a few specific locations: brain, eyes, testes/prostate.

- Check out Figure 7 from this ASM Clinical Micro Review for a look at concentration in tissues and body fluids for antifungal agents (relative to plasma): Felton T, Troke PF, Hope WW. Tissue penetration of antifungal agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27(1):68-88. doi:10.1128/CMR.00046-13

- Do you have the right drug at the right dose?

- Do you not have an expected response to therapy because there is misunderstanding about the host’s immune response?

“When there is a cat in the history, it is always to blame” — Classic cat-associated infections

“My cat loves PPeanut BBuTTTer”

- PP = plague (Yersinia pestis), Pasteurella

- B = Bartonella, Bordetella bronchiseptica

- TTT = Tularemia, Toxoplasma, Toxocara cati

Want a more comprehensive resource for locating information on infections associated with different activities or animal exposures? Here is a look at Infections of Leisure, Fifth Edition by David Schlossberg in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

A quick summary of definitions in endophthalmitis given this episode’s patient case

- Endophthalmitis indicates an infection within the eye and usually implies infection of vitreous and/or aqueous (within the globe)

- Endogenous endophthalmitis results from hematogenous seeding of pathogen into the eye

- Exogenous endophthalmitis is due to infection introduced from “outside,” such as surgery, trauma, or extension from cornea (aka keratitis)

- Typical symptoms: decreased vision, pain, hypopyon. Fungal cases are sometimes described as having “fluffy” vitreal lesions

- Fungal endogenous endophthalmitis is typically due to Candida but can occur rarely with other fungi. Endogenous mold endophthalmitis is commonly associated with immunocompromised hosts or intravenous drug use.

- Quick high yield notes on management of endophthalmitis:

- Echinocandins have poor eye penetration

- Fluconazole has good eye penetration (but can use other azoles)

- Fungal endophthalmitis is a very challenging diagnosis, and early diagnosis is critical to preservation of vision. The prognosis is quite variable. Surgical / Intravitreal treatment is often needed, and vitrectomy or enucleation is not infrequent in severe fulminant cases

- For a few papers related to Aspergillus endophthalmitis specifically:

- Here are 3 cases of endogenous Aspergillus endophthalmitis followed by a literature review of cases published in English from 1949-2001. Riddell Iv J, McNeil SA, Johnson TM, Bradley SF, Kazanjian PH, Kauffman CA. Endogenous Aspergillus endophthalmitis: report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2002;81(4):311-320. doi:10.1097/00005792-200207000-00007

- Recent paper that summaries diagnostic and management strategies. Spadea L, Giannico MI. Diagnostic and Management Strategies of Aspergillus Endophthalmitis: Current Insights. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019;13:2573-2582. Published 2019 Dec 24. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S219264

Beta-D-Glucan (BDG) / Aspergillus Galactomannan (GM)

- Beta-D-glucan has been shown to be clinically useful in diagnosis of invasive fungal infection, especially if levels are significantly and repeatedly high — but it cannot be interpreted on it’s own. The results must be synthesized in light of the clinical presentation and with consideration for possible causes of false BDG elevation. Keep the chart below for reference when you think about beta-D-glucan and Aspergillus galactomannan

- The IDSA guidelines for aspergillosis recommend use of serum and BAL GM as well as BDG for diagnosing IA in high-risk patients (hematologic malignancy, allogeneic HSCT) in particular.

- Serum GM is not recommended for screening in SOT recipients, patients with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), or those on mold-active antifungal therapy or prophylaxis (but potentially can be used in bronchoscopy)

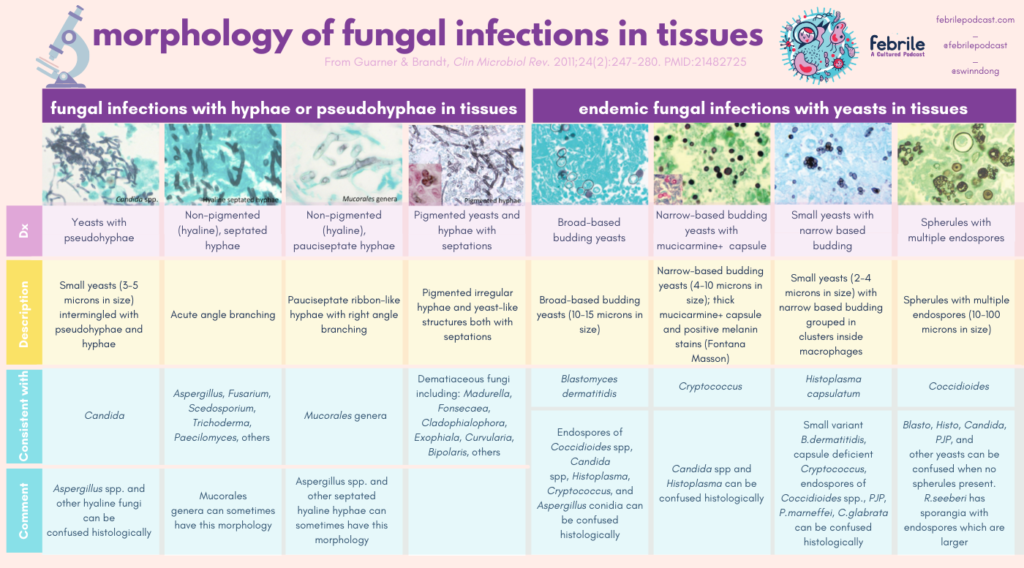

Using histopathology from tissues to diagnose fungal infection can be tough. Here is a great resource to keep for reference when you are trying to use morphology in tissue. I’ve converted the major charts from this paper in the graphics following the link!

“When I hear fungal endocarditis, I cringe because I know the increased morbidity and mortality.” Let’s briefly think about fungal endocarditis (FE) here.

- Most common cause of FE is C.albicans, followed by: non-albicans Candida, Aspergillus, Histoplasma, others.

- The most common risk factors typically identified historically included prior valve surgery, rheumatic heart disease, vascular lines, and host factors. More recently, there seems to be a shift more towards invasive lines, noncardiac surgery, immunocompromised hosts, and IV drug use.

- FE has a very high mortality. In one study, there was a 55% mortality with combined medical/surgical treatment vs 36% with antifungal alone. The major caveat here is that the majority of patients were treated with Amphotericin B.

- FE has a high risk of embolization

- Diagnosis is also difficult as blood cultures are negative in the vast majority of cases.

- Take a closer look here, this is a review of FE cases over a 30 year window. Ellis ME, Al-Abdely H, Sandridge A, Greer W, Ventura W. Fungal endocarditis: evidence in the world literature, 1965-1995. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(1):50-62. doi:10.1086/317550

In this following section, we’ll cover a few points about Aspergillus.

IDSA Guidelines for Aspergillus are available here, last updated in 2016:

Key classic risk factors for Aspergillus infection:

- Severe and prolonged neutropenia

- Corticosteroid use (typically high doses +/- prolonged duration)

- Chronically impaired cellular immune responses or severe immunosuppression (e.g. allogeneic HSCT, SOT, advanced HIV/AIDS, CGD or other immunodeficiency)

How long to treat?

- Treatment durations for the various Aspergillus syndromes are outlined in Table 1 of the IDSA guidelines

- Generally antifungals are continued until signs and symptoms of infection and immune dysfunction are resolved. For most immunosuppressed patients, antifungal therapy will be continued for months or even years. The total duration of therapy is dependent on:

- Degree and duration of immunosuppression

- Site of disease

- Evidence of disease improvement (such as radiographic abnormalities)/ Response to therapy

- Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is treated for a minimum of 6-12 weeks, but typically much longer in patients who are immunosuppressed. For those with endocarditis or other severe forms of infection (such as brain abscess), many would give lifelong suppressive antifungal therapy with oral triazole.

What about the use of combination antifungal therapy for invasive aspergillosis (IA)?

- First off is ensuring that you have gone through the exercise of examining the current plan. Think about the antifungal therapy: is the antifungal choice, dose, penetration, etc. appropriate? is the med correct? What about the infection: is there a co-pathogen? And so on.

- Combination antifungal therapy has been evaluated both as initial therapy and salvage therapy for IA. Currently, the IDSA guidelines mention possible use of combination therapy with voriconazole and an echinocandin in select patients for salvage therapy (weak recommendation, moderate-quality evidence). Combo antifungals for primary invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is not routinely recommended, but recommended to consider echinocandin with voriconazole for primary therapy in setting of severe disease (particularly if hematologic malignancy or profound/persistent neutropenia)

So you decide to consider combination therapy for your patient, what information is out there on efficacy and safety of antifungal combination therapy for invasive aspergillosis?

- The combination of polyenes or azoles with echinocandins has been studied the most, with an additive or synergistic effect in majority (but not in all) when compared to monotherapy.

- Preclinical studies include in vitro studies (investigating antifungal susceptibility and interactions between antifungals) and animal studies

- In vitro studies have been variable, ranging from synergy to antagonism. Limitations here: No CLSI protocol for in vitro synergy testing of fungi, plus the lack of correlation between in vitro synergy data and clinical outcomes.

- Animal models have had contradictory results. Studies demonstrated a possible trend toward improved survival when compared to monotherapy with echinocandins, but no benefit compared to monotherapy with voriconazole.

- So what about clinical studies?

- Clinical series have been summarized in some of the articles noted below, such as Table 1 in Martin-Pena, et al., CID, 2014. The drawbacks to these include:

- Limitations in quality of study design

- Usually retrospective, single-center

- Variable patient populations, antifungal agents used, durations

- Absence of a true measure of efficacy (measurement of satisfactory response is difficult to measure, particularly when looking retrospectively)

- Comparisons to historical controls (improvements in early diagnosis and therapy will impact outcomes of those who are treated in more recent time periods)

- Here are the clinical trials evaluating combination therapy with IA.

- Maertens J, Glasmacher A, Herbrecht R, et al. Multicenter, noncomparative study of caspofungin in combination with other antifungals as salvage therapy in adults with invasive aspergillosis. Cancer. 2006;107(12):2888-2897. doi:10.1002/cncr.22348 — Open-label, non-controlled, noncomparative multicenter trial of efficacy and safety of caspofungin-based combinations for salvage therapy in 53 pts with IA. No differences in endpoint of ‘favorable response’. Results not compared to monotherapy.

- Caillot D, Thiébaut A, Herbrecht R, et al. Liposomal amphotericin B in combination with caspofungin for invasive aspergillosis in patients with hematologic malignancies: a randomized pilot study (Combistrat trial). Cancer. 2007;110(12):2740-2746. doi:10.1002/cncr.23109— Pilot, randomized, comparative study of liposomal Amphotericin B monotherapy (10 mg/kg!) vs LAmB (3 mg/kg) with caspofungin for initial therapy of probable or proven IA in 30 pts with hematologic malignancy. More favorable responses in combination group, but not surprisingly, increased adverse effects of nephrotoxicity with high dose AmB in monotherapy arm

- Marr, et al – summarized in more detail next

- Clinical series have been summarized in some of the articles noted below, such as Table 1 in Martin-Pena, et al., CID, 2014. The drawbacks to these include:

- The most suggestive evidence is probably for voriconazole + echinocandin. Let’s take a look at this trial: Marr KA, Schlamm HT, Herbrecht R, et al. Combination antifungal therapy for invasive aspergillosis: a randomized trial [published correction appears in Ann Intern Med. 2015 Mar 17;162(6):463] [published correction appears in Ann Intern Med. 2019 Feb 5;170(3):220]. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):81-89. doi:10.7326/M13-2508

- Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial (93 international sites) to assess safety, efficacy of voriconazole +/- anidulafungin for primary treatment of IA in 459 patients with hematologic malignancies (HM) and/or HSCT

- Primary outcome = 6 wk mortality

- In intention-to-treat analysis, there was no difference in 6-week mortality between groups (20.6% vs. 23.5%)

- Among the 277 patients with documented proven or probable IA though, there was a trend toward improved 6 wk mortality with voriconazole + anidulafungin (19.5%, 26/135) vs. voriconazole monotherapy (27.8%, 39/142), p=0.087.

- In a post-hoc analysis, subgroup of patients diagnosed with probable IA based on radiographic abnormalities and positive serum or BAL GM positivity had a significantly lower mortality with combination therapy vs voriconazole monotherapy (16% vs 27%, p=0.037)

- Safety measures including hepatotoxicity were not different

So the question of combination antifungal therapy in IA is not easy, as there is no data demonstrating clear superiority of it’s use. Although only some of the studies addressed toxicity of the combination regimens, it does seem that azole-echinocandin regimens are tolerated fairly well. Like everything else in medicine, it requires balancing the risks and benefits of dual drugs — weighing toxicity, severity of disease, degree of immunosuppression, risk of death, cost, patient factors (such as ability to use IV medication if needed).

Check out these references:

- Here is an analysis of the available information on combination antifungal therapy for IA from 2014: Martín-Peña A, Aguilar-Guisado M, Espigado I, Cisneros JM. Antifungal combination therapy for invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(10):1437-1445. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu581

- Here is a comprehensive Clinical Microbiology Review on use of combination treatment of various invasive fungal infections. You can check out the section “Antifungal combinations against Aspergillus and Fusarium species” (180-184) and Table 5. Mukherjee PK, Sheehan DJ, Hitchcock CA, Ghannoum MA. Combination treatment of invasive fungal infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(1):163-194. doi:10.1128/CMR.18.1.163-194.2005

- This article from Transplantation discusses combination antifungal for IA and mucormycosis in transplant recipients. Figure 1 has a proposed approach to combination antifungal therapy for IA in SOT patients from the authors. Haidar G, Singh N. How We Approach Combination Antifungal Therapy for Invasive Aspergillosis and Mucormycosis in Transplant Recipients. Transplantation. 2018;102(11):1815-1823. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000002353

- A 2014 meta-analysis of clinical studies. Panackal AA, Parisini E, Proschan M. Salvage combination antifungal therapy for acute invasive aspergillosis may improve outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;28:80-94. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2014.07.007

Other miscellaneous mentions and notes:

- Examining Occam’s razor, Hickam’s dictum, and Crabtree’s bludgeon. Mani N, Slevin N, Hudson A. What Three Wise Men have to say about diagnosis. BMJ. 2011;343:d7769. Published 2011 Dec 20. doi:10.1136/bmj.d7769

- Like textbook references?

- Mandell, Principles and Practice of ID, 8th Ed.:

- Chapter 259: Aspergillus species

- Chapter 116: Endophthalmitis

- Long, Principles and Practice of Pediatric ID, 5th Ed.:

- Chapter 244: Aspergillus species

- Chapter 84: Endophthalmitis

- Mandell, Principles and Practice of ID, 8th Ed.:

Episode Art & Infographics

Goal

Listeners will be able to evaluate a patient who presents with concurrent brain and lung lesions.

Learning Objectives

After listening to this episode, listeners will be able to:

- List a comprehensive differential diagnosis for infectious etiologies of concurrent brain and lung lesions, including bacterial, mycobacterial, parasitic, and fungal causes

- Implement approach to identify possible causes of poor response to antimicrobial treatment

- Interpret clinical use of beta-D-glucan testing for invasive fungal infection

- Describe the evidence for use of combination antifungal therapy in invasive aspergillosis

Disclosures

Our guest (Gerome Escota) as well as the Febrile podcast and host (Sara Dong) report no relevant financial disclosures.

Citation

Escota, G., Dong, S. “#2: Brains and lungs and eyes, oh my!”. Febrile: A Cultured Podcast. https://player.captivate.fm/episode/8af81a5a-0ce5-40e3-a35d-2e8d43fec71a